Now Available: "Paradigm Shift: Paradigm Slippage: Paradigm Boogie-Woogie" (Retcon, movement 2, installment 2)

An Announcement with Miscellaneous Notes, Excuses and Diversions, including a Brief Introduction to the Star Gauge of Sū Huì

If anyone is tracking things, you’ll have noticed that the second story of the second movement of my mosaic story Retcon was appallingly delayed. But I am delighted to be able to announce that it is now, finally available in fine ebook stores everywhere! You can buy it at my web site (where you can buy just the individual ebook or buy a subscription to the whole series, including all past & future issues), or you can buy it at Amazon (including non-US Amazons like Amazon UK), Apple, Barnes and Noble, Kobo, and Smashwords. Here’s the cover:

That is the basic of this post: the story (a novella really, it’s over 28,000 words long) is available, go read it. There’s a lot more words, but none of them are as good as the words in the story, so only read on if you need convincing and/or have already read the story and are curious about some of the details that make up the margins of the story —no spoilers, just behind-the-scenes chatter. In fact, the first part is a general reintroduction to Retcon as a whole; if you remember about the series and just want the behind-the-scenes chatter about this particular installment, jump to here. (The most independently interesting, only-a-minor-connection-to-the-story section is here.)

But go read the story!!

It’s Been A While. Remind Me What This Whole Retcon Thing Is?

Retcon is my current major creative project, a mosaic story (that is, a story made up of smaller stories) projected to run for twenty-seven stories in three movements (think a series of a TV show or a particular run of a comic) of nine stories each. As with other mosaic stories, the individual stories build upon each other, but they also differ in focus (so the main characters in one will be minor characters in another, and vice-versa), in genre, in format, etc—a (hopefully) playful and fun variety.

As of this most recent publication eleven stories are now available: the entirety of movement one, Necessity, and the first two installments of the second movement, two, Contingency. Here’s a list of the stories so far:

Necessity:

Zero Second

Years Scattered Like Fallen Leaves

Xu Ming’s Second Time Down

While Unbeknownst to the Rest the Woman in the Yellow Dress Was Also a Time Traveler

Very Soon And Yet Still Very Far Away

Unless Another Escape to Tell Thee

Thus in Time Are We All Devoured

Screaming in Circles

Retcon

Contingency:

Quartet for the End of the Beginning of the End of Time

Paradigm Shift: Paradigm Slippage: Paradigm Boogie-Woogie

Ordinal Unknown (forthcoming autumn, 2025)

The stories started out as short stories—well, technically novelettes as professional writers reckon these things, but short stories to the general reader1—but all of the recent installments have drifted over to the realm of the novella.

Fine, but what’s the story about?

A fair question! Well, here’s the blurb I wrote for the series as a whole:

In 1951, a pair of scientists at Cornell University discovered time-travel. With the specter of the atomic bomb in the immediate background, they decided not to replicate Einstein’s mistake of informing the political authorities about something that might turn out to enable a terrible weapon to be built. Instead, they decided to set up a clandestine research program, investigating the phenomenon, while swearing all those who came to work on it to utter secrecy.

Forty years later, in 1991, a time traveler returns from forty years further into the future 2031 with some disturbing news: no traveler and no message has ever come from any later point in time than the moment at which that time traveler themself left: April 4, 2031, at 3:56 in the afternoon. No one knows why. All they know is that something must have happened to prevent anyone from traveling or messaging further back beyond that point—a point they come to refer to as “zero second”.

This is the story of what happens next… if “next” is the right word for a narrative which, in the way of things, is necessarily non-linear.

Obviously, in a long story—and this will fill three fat books once it’s done—the story is not about one thing all the way through, but that’s the starting point.

Wait, Do the Movements Have Titles?

Oh, you noticed that, attentive reader? Well, yes. This is a story in 27 stories, but it is also a story in three movements, and each of those have a title (which will be the title for the collections when, eventually, it becomes a trilogy of books. Someone who is good at marketing2 would have had a Title Reveal, but I never got my act together to do that, and sort of let them slip here and there—not so you’d have noticed necessarily, but enough that it wasn’t a Big Reveal. But yes, the movements have titles. The first movement as a whole is entitled Necessity. The second movement is entitled Contingency. And I will hold the third title back for a while, as a feeble and probably misguided attempt to do Marketing.

Did You Just Imply That There’s Going to Be a Print Copy at Some Point?

There will be: I will gather up each movement (nine stories each) and publish them as a trilogy of both ebooks and as actual print books. There will be a few extras in the collected volume, too. (Anyone who subscribes to the series as a whole will receive an ebook copy of the collected volumes as part of that subscription.)

When will they come out?

Well, I just was months and months late on a single !@#$% installment. I am not making any promises about the collected editions! The best I can say is: as soon as The Accident3 allows.

And when they do, volume one will be titled Necessity and volume two will be entitled Contingency.

Enough About This Series as a Whole, What’s This Particular Story About?

All right, I will again share a blurb, in this case the blurb to this specific story:

It's the same old story: Girl Meets Boy, Girl Looses Boy, Girl travels through time and meets herself, and Boy again, only it's not quite the same Boy, and… er, try again: It's the same old story: You're trying to change the world, but it's trying to change you, too, and it wins, and it's you that's changed and not the world, only you're part of the world so it's different, too, and watch the sexes of the Professor and Doctor because something fishy is going on there… er, take three: It's as easy as ABC: A is for Beginnings, B is for Fallback Options, C is for Average. Things are changing, and it's hard to find love and make the world better when standing on shifting sands. Same old story, right?

That blurb is—you might have noticed—terrible. (In general, I suck at blurbs.4) It’s main virtue, I think, is to be cute for anyone who reads it after reading the story: the precise opposite of what a blurb is to be. So let me just say this is a story about love and research in a time travel universe, and leave it at that.

Tell Me About the Cover

I have, of course, committed the sin of photocomics before; while I am mostly a penitent to this particular sin, I figured that one set of sequential images (among the 27 that will make up the covers to the individual stories) was not too much, and after due consideration I decided to “spend”, as it were, my one comics cover on this installment.

The reason is fairly straightforward. As I’ve said before, I tend to view the covers as illustrations less of the story per se than of the title—so that you can think of the entire work as a diptych, with one photograph and one story both on the same theme. Well, in this case the title— “Paradigm Shift: Paradigm Slippage: Paradigm Boogie-Woogie” was all about change, and a series of increasingly skew changes. So a comic seemed the best way to capture that:

The idea is to capture, in still images, a magic trick: a real rose is turned into an origami rose; the rose is set on fire; the flaming rose becomes a bird (in this case, our late, beloved pet lovebird, Snark, whose name of course also graces the name of the press which publishes both Happenstance and Retcon5). I am reasonably pleased with how the image came out, with one potential issue, namely, that I am not sure the image is quite as legible as I had hoped: in the third panel what you are seeing is a real rose, but in the fifth it’s an origami rose. But I fear that my beloved family (whose members collaborated on its construction) did it too well, and it looks too much like the rose. It’s supposed to look a tad artificial! (I hope, of course, that i am wrong about this.) In the future, I will make sure to engage sufficiently incompetent origamists for any such project I might embark upon.

Is There Some Funny Story About the First Epigraph(s) To This Volume?

Why, yes, there is, how funny you should happen to ask.

There are two (arguably three) epigraphs to this story. Here is the first one (or, depending on how you count, the first two):

Of true things, one knows the end and the beginning.

From the beginning to the end, one knows the truth of things.

— Two possible readings of a line from the reversible poem The Star Gauge by Sū Huì, translated by Michelle Metail & Jody Gladding

This will probably take a little explaining.

First of all, it is from a book by French author (and Oulipian) Michèle Métail, which was then translated into English by Jody Gladding under the title Wild Geese Returning: Chinese Reversible Poems. Métail’s book is a combination of analysis and discussion of the form and a selection of the poems, so the poetry is (presumably? I don’t think it’s clarified) an English translation of a French translation of (classical) Chinese poetry. (That’s why I described it as a joint translation.)

Reversible poems are this amazing cultural artifact. My sense is that they are enabled by the unusual structure and nature of classical Chinese—they are apparently possible in contemporary Mandarin (the book mentions that “a few examples of circular poems sometimes appear in journals, under the rubric of games or curiosities”, but adds that “they do not figure into recent official histories of Chinese literature.” The book, however, contains examples running from the fifth century up through the end of the Qing dynasty (1911). It is, frankly, amazing and cool that such things exist at all.

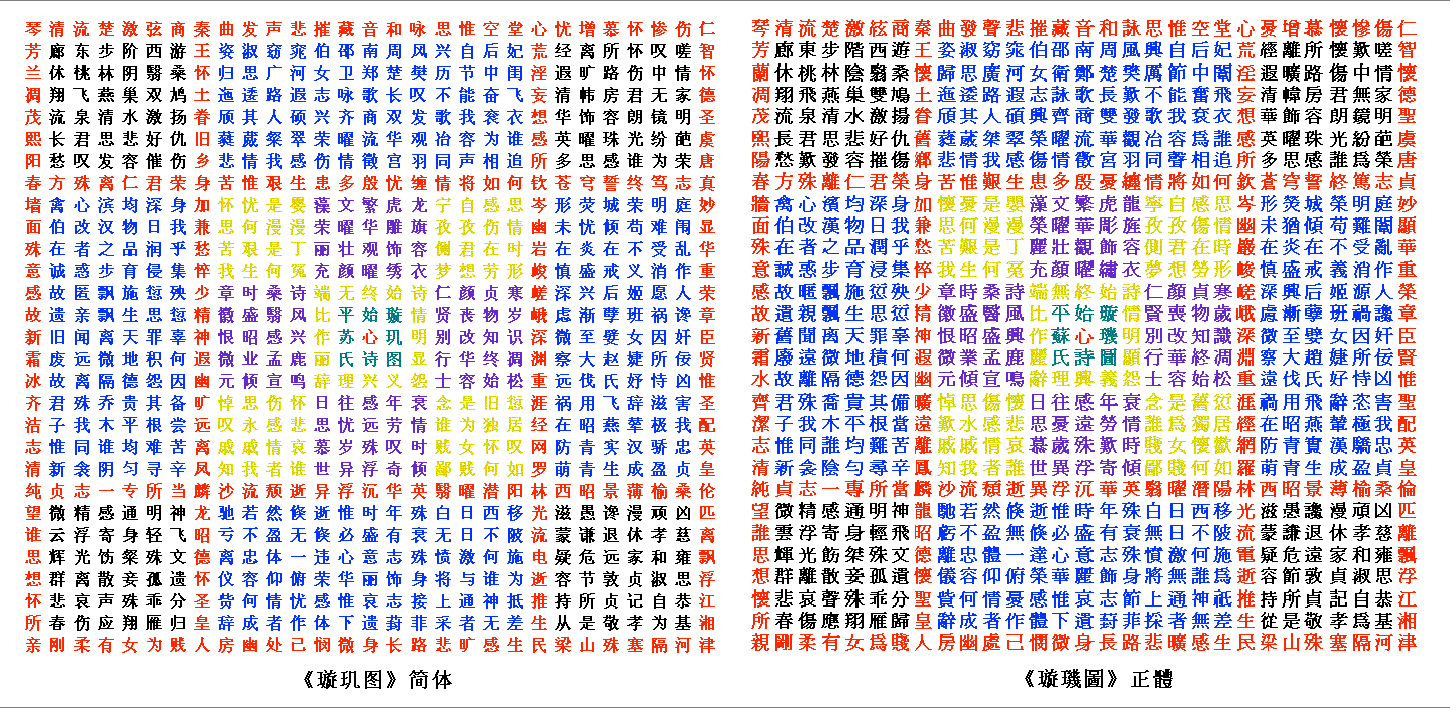

— But the very first such poem is the most amazing of all. The form was invented by a fourth-centurty poet named Sū Huì (also called in the book Su Shi, for reasons which are not quite clear to me, although confusingly enough there is a different Chinese poet from seven centuries later of that name). The later poems were “mere essays in the craft”, but Sū Huì created a flat-out masterpiece, which contains (depending on who’s counting) at least 200 and possibly as many as 12,820 different poems, when read in different (quite reasonable) orders. (It is worth recalling, in this context, that classical Chinese did not have a standard reading order, and could be written and read left to right, right to left, top to bottom, or bottom to top, so that all these orders were, in that context, perfectly natural.) Here’s a picture of the poems, with subsections highlighted in different colors. Note that this gives the entire poem twice, once on each side: the left side is in the simplified characters currently in use in mainland China, and the right side is in the traditional characters that Sū Huì would have written.

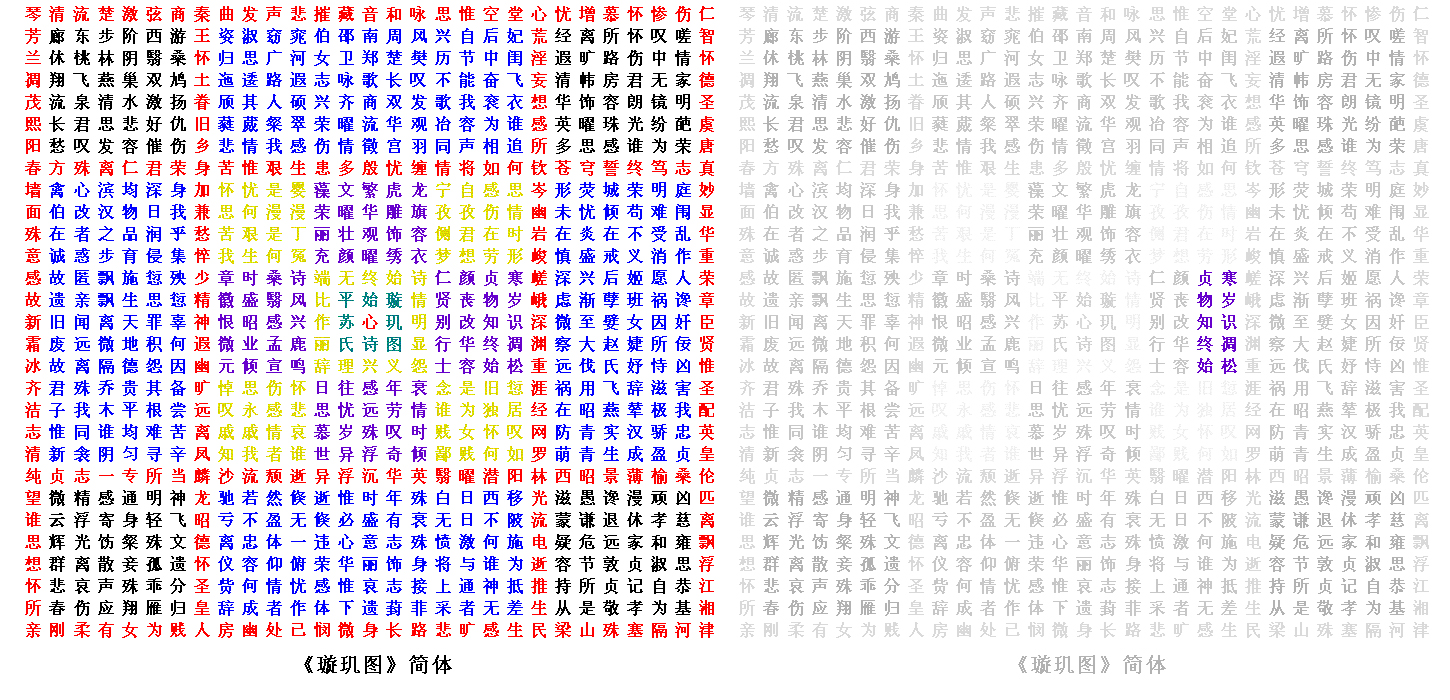

If you’re curious, the line I quoted two versions of (贞 物 知 终 始) is in the right-side purple section (near but not in the middle); it is the third of the four lines, counting from the middle out, which is to say the innermost of the two highlighted below:

I chose this epigraph because, of course, it fit the story, but I can’t deny that I was also swayed by the fact that the line could be read in two such different ways, which seemed appropriate for a “paradigm shift” story. I considered using a longer excerpt, but went with only the section that really fit the story I was writing. But here are two versions of the quatrain (i.e. the entire block of four lines that the single line is from):

From the beginning to the end, one knows the truth of things: The beauty of a face is transformed by the despondency of the look; The literati who leaves wanders far from the virtue of the sage; In the pine that wastes away, one recognizes the cold of the year.The cold year is recognizable in the dead pines; The virtuous sage is distinguished from the wandering literati; The depressed look transforms a beautiful face: Of true things one knows the beginning and the end.— Two (of sixteen) possible readings of one section of Sū Huì's poem The Star Gauge, translated by Michelle Métail & Jody Gladding

Note that Métail does not give all sixteen possible options, but since each individual line can be read in only two ways, with the versions she does give you can reconstruct all sixteen possible readings. (Which, it is worth noting, is not every possible combination of two variations of four lines.)

In general, Métail gives only small, wonderful snippets of the poem. It is clearly not possible to present a full translation in a way that would read at all naturally. But since any given line has (I think). only two readings—the number of poems comes from the combinatorics of the different orders in which the lines can be combined—it should be possible to lay them out, giving two readings of each line, and then instructions for how one is reasonably able to combine them.

Métail’s book is wonderful and I recommend it to all.

What’s Up With the Second (or maybe third) Epigraph?

Here’s the other epigraph (I think of it as two, not three) to the story:

I passed a stranger on the street And from this one I'd never meet Arose a world within my mind Where we were lovers, souls entwined. I saw us amble, arm in arm, Just to taste air's early charm, And saw in each routine day's kiss An earthly scrap of heaven's bliss. Then round a bend the stranger danced: The world birthed from a second's glance Dissolved into the mind's chill air And left no mark but trace of care.— W. H. Auden, unpublished fragment from some other timeβ

This is, of course, not anything Auden wrote in our familiar timeβ, but there is some version of timeβ in which he did, and I have quoted it from that.

(This is not the first time I have quoted a verse which is not quite from the poet I have associated with it—the other is the epigraph to the story “While Unbeknownst to the Rest the Woman in the Yellow Dress Was Also a Time Traveler“, which no one has yet noticed, but which I admit I rather liked—and it will not be the last, either.)

What’s Up With The Sub-Section Titles In the Story?

It was fun, and (in several different senses) they fit. Beyond that, res ipsa loquitur.

Do The Sub-Section Titles Give a Clue As to How A (Reverse) Abecedary Will Have Twenty-Seven Parts?

Yes.

If you scroll back up and look at the story titles—particularly the first letter of each of the story titles—you will notice a pattern. If you then remember that this is a 27-story series (not a 26-story one)—three movements of nine stories each—then you might wonder how this is going to work. If you read the latest story, there is a Clue. (Or what’s more obvious than a clue? A giveaway?—one of them.)

Although if, before planning out this series, I had read Kathryn Schulz’s marvelous memoir Lost and Found—which of course I couldn’t have, since it was only published once the series was well underway—and, in the course of reading it, encountered this passage:

Until the late nineteenth century, the final character of the English alphabet was not the letter Z but a word: “and.” That word was written—on countless slates and blackboards and grade school primers—as “&,” so that the whole sequence looked like this:

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z &

The twenty-seventh of those symbols dates back to ancient Rome, when scribes, resorting to cursive to write more rapidly, linked the two letters in “εt,” the Latin word for “and.”… It makes sense that this stray character got appended to the English alphabet. Students had to learn to read and write it, after all, and it was at least as tricky to form as R or Z. The fact that it represents an entire word was hardly disqualifying; so can A and I and even O (as in “O Come, All Ye Faithful” and “O death, where is thy sting?”). But the “&” did present a unique problem. If you recite the alphabet with it stuck to the end, as schoolchildren across the English-speaking world were routinely required to do, you sound as if you are leaving your listener hanging: “…X, Y, Z, and.” And what? It’s not true, no matter what old-fashioned grammarians might tell you, that you shouldn’t start a sentence with “and,” but ending something that way is a different story. To solve this problem, students were taught to use the Latin phrase per se, meaning “in itself,” to indicate that they meant the character, not the word. Thus instead of saying “X, Y, Z, and,” they dutifully said, “X, Y, Z, and per se and”—a phrase that, over time, grew blurry from repetition. It is our language, then, that turned the Latin “&” into the ampersand.

— Then I might have squared this particular circle differently.

Perhaps for another abecedary.

Like Métail’s book, Shulz’s book is marvelous and I recommend it wholeheartedly.

After, of course, you’ve read my story,.

You’re Going to Give Us the Links to Buy the Story Again Before the End, Aren’t You?

Of course:

You can buy it at my web site (where you can buy just the individual ebook or buy a subscription to the whole series, including all past & future issues), or you can buy it at Amazon (including non-US Amazons like Amazon UK), Apple, Barnes and Noble, Kobo, and Smashwords.

Or they should be. In some communities—SF fandom high among them—the technical writer’s definitions have spread, which strikes me as, roughly, a bad thing: the difference between short stories and novels is, of course, important and worth noting; that of microfiction and the novella from either is probably too; but “novelettes” is a bridge too far for any purposes but making sure there are enough award categories.

I suck at marketing. I really, really, really suck at marketing. This is something a wise man would have taken into account before doing something like self-publishing a long, ambitious work of fiction.

™ Kurt Vonnegut.

This is a subsidiary fact of the general reality that, as mentioned (see above, note 2) I suck at marketing in general.

Just his name: the press’s icon is a picture of his companion, the late Boojum.