DONALBAIN What is amiss? MACBETH You are, and do not know ’t. The spring, the head, the fountain of your blood Is stopped; the very source of it is stopped. — Macbeth 2:iii

My dad precisely died a month ago, on November 7, in the early morning. He had been in good health (at least for a man of 84) until last April, when a middle-of-the-night fall began the series of events which culminated in his death.

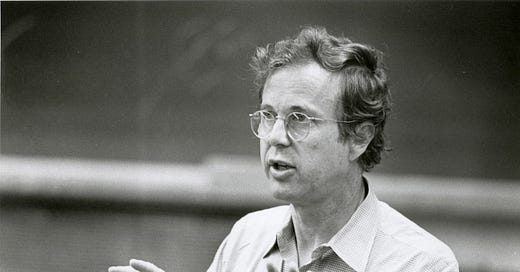

The Harvard Law School (where he was on the faculty for more than forty years) put up an obituary for him here, which does a good job over covering his professional accomplishments.

Tonight is (according to the Jewish calendar) the one-month anniversary of my father’s death. It thus either is the shloshim (i.e. the one month anniversary) or it concludes the shloshim (i.e. the first month of mourning)—I have heard the word used in both ways.1 So it seemed fitting to try and pull myself together and publish something today.

On the twentieth anniversary of my mother’s death, I (re)published the eulogy I gave for her at the memorial service four days after her death. (If anyone happens here who doesn’t know about how my mother died, that link will explain, which in turn will make one section of the below make more sense.) So I have decided to publish here the eulogy I gave for my dad two days after his death.

I do so with some hesitation. First, there were four speakers at the funeral, of whom I was only one (the others were my sister, Emily Frug Klineman, and two friends and colleagues of my dad, Chris Desan and David Kennedy). In the case of my mom’s eulogy, it had already been published along with the others; in this case I don’t have the right to publish any but my own. And I think that the four together gave a much better view of my dad than does mine standing alone. Nevertheless, this is what I, in the immediate aftermath of his death, had to say, so I will put it up here, just as I put up another years ago.

My second hesitation is that in the delivery, when I spoke about his voice, I actually used his characteristic vocal inflections and rhythms; I think it was a key part of what made that section work. Obviously I can’t reproduce that here, and it wouldn’t mean much to those who don’t know him (obviously most of those at the funeral did (not-so-obviously, not everyone did)). But this is unavoidable, and after thinking it over I decided that it’s not such a hindrance as to forestall my publishing it.

And finally I hesitate because I know as well as anybody that performing grief is a difficult task, one that requires care and craft that I am not sure I am properly summoning right now. For a loss this great—as the loss of any parent is great, but also uniquely as the loss of this particular man is,2 this particular human who was “of all those of his time whom we have known, the best and wisest and most righteous man”3—lamentations that would ring the world and darken the heavens are called for. But all I have are my own poor, threadbare and exhausted words. Tread softly, for you tread on my grief.

Still, despite all this, I think it worthwhile to make my initial foray public for those who might want to read it.

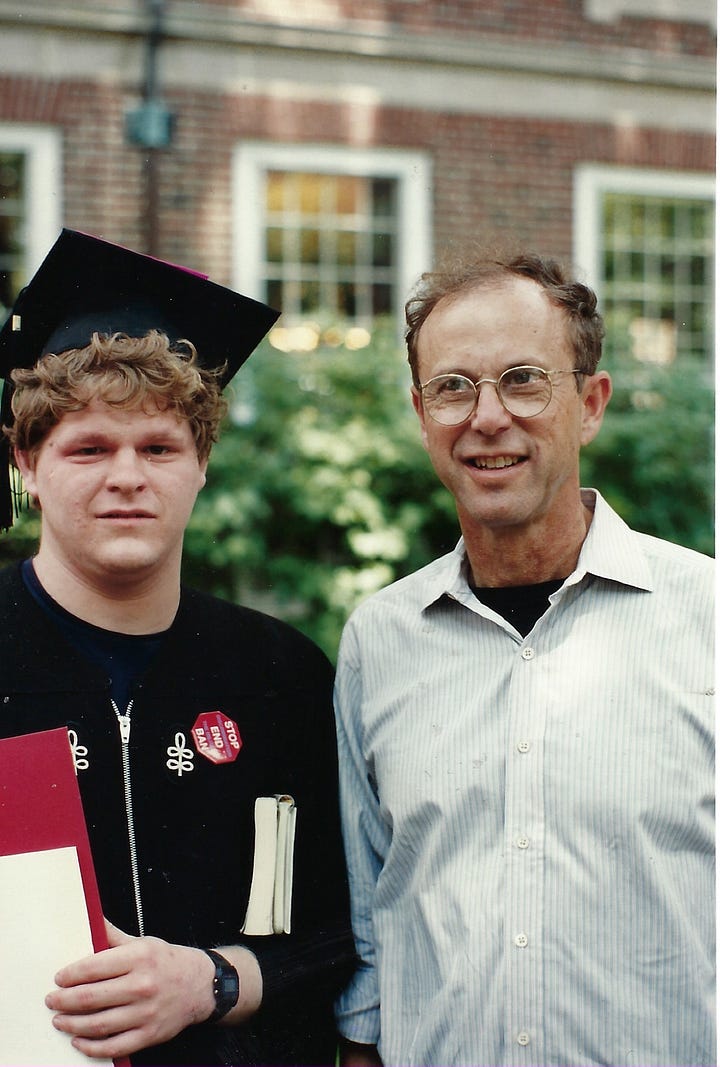

The eulogy as delivered4 starts after the below photograph, and runs to the next set of images.

Eulogy, Delivered November 9, 2023

I'm here to speak about my dad.

My father was a man of many talents, one of which was as a eulogist. This is not a genre in which anyone wants to attain great mastery. But as the occasions piled up, he demonstrated a real skill at it, speaking about his own father, and his mother, and our grandmother Ruth Gaw; about his friends David Charny and Gary Bellow. He told me on a number of occasions that the rules for a good eulogy were simple: say only true things, and say only good things. Fortunately for me, this is not a high bar to clear in my father's case.

My father was, as I think almost everyone here knows, passionate about many things: about law, about cities, about making people's lives better, and making the way we live together work better; about art, particularly photography; about music; about travel. And of course about people: his students, his colleagues, his friends, my friends and Emily's friends; his plumber; the caregivers who cared for him in his final months; and, of course, his grandchildren, all three of whom he loved deeply.

Rather than speak about any of these multiple passions separately, I want to speak about a few things that carried through all of them.

The first and maybe the foremost is his voice. I mean this both in the sense of his particular intonations and way of shaping sentences, but also in the words and phrases that he used, and habits of speech he returned to. I'm sure that everyone who knew him heard him say at some point that we have to "figure out" something, or say in a non-legal context "the cases are distinguishable", or tell them to "keep me constantly informed", or talk about the X/Y distinction, where X and Y can be anything—public/private, father/grandfather, friend/colleague, whatever it is.

And it was more than small turns of phrase. A characteristic mix of ironies, paradoxes, and comic overstatements joined together into a complete way of speaking. When discussing the constitution, he might say, "Well, when I was in Philadelphia in 1787, I thought...". Or when someone told him about something, they would be said to have "invented" it—like so-and-so invented this restaurant, or invented this person, or invented this book.

His voice was then echoed by others. A great many of his colleagues, and maybe students, would speak in the intonations, phrases, and habits of thought that were characteristic of my father. It went both ways; I'm fairly sure that "too strong" from Nathaniel Berman. But for the most part it was his, and he melded it together and joined it together into a way of thinking and approaching the world that was uniquely his. And it became a way that many of his friends and his colleagues spoke and thought about the world, the way his family spoke and thought about the world. The way I do.

But for me the most remarkable thing about my father's voice is that as far as I can tell he didn't get it from anywhere. I look at myself and my sister and I know where we get the way that we speak and the tone and phrases that we use; I know where our kids get them; I know where his colleagues get them. But my father's parents and his brother, dear as they were to him and to us, didn't speak anything like this. His colleagues, as I said, influenced his speech, but none of them had it in his way—he did not learn it from them.

In ancient Greek thought they said that Athena burst fully-formed out of the head of Zeus. I think my father burst fully-formed out of his own head.

My father was also a man of extraordinary good, practical sense. Of course my sister and I came to him for advice, but so did everyone else: his colleagues, his friends, his students, our friends, and nearly everyone. And whenever you had a practical problem—like, 'how do I come out to my parents who I fear might disown me'; or, 'my sister needs to find an apartment in London, how can we do it in a way that she can afford it'. How do you get into a new career? How do you buy a car? How do you pick out flowers to bring to a grave—or, for that matter, how do you give a eulogy? He would think it through, and cut to the heart of the matter, what you needed to "figure out" in order to make it work.

You might think that this good practical sense was very different than his intellectual pursuits, in which he was so playful and so dramatic. But I think in some ways his intellectual pursuits arise from that same very practical good sense. He would sit down to an intellectual task—to write an article, to edit an article that someone else gave him, to teach a class, to help someone else figure out how to teach a class—and he would think what needs to be done to get this to really work? What are the key points that need to be figured out? Once my father, later in his career, joined a team of architects on a project, a theoretical design for a display. Now he was not in any way an architect, but apparently he contributed enormously to it, and even when he wasn't there, they used to say, now what would Jerry say about this situation? Because he had a way of thinking, of getting to the heart of things, that transcended any particular endeavor. For all his love of postmodernism and play, of art and artifice, of ideas and texts, he never forgot, and never failed to center, the realities of being human in a complex and painful world—and how we can make it better.

I feel like I can't properly eulogize my father without mentioning my mother. April 4 drew a horrible scar across his life, as it did all of lives. He often spoke to me of the three chapters of his life: before Mary Joe, his time with Mary Joe, and then after Mary Joe, which slowly over time lengthened to equal first one and then the other, than to exceed them both. She was a palpable absence for much of his life. One of the most wonderful things he did as a scholar was to take her work, including the article that she was writing and even the sentence that she was halfway through, and compile them, and get them into law reviews and collect them into a book and get her casebook published. And of course he worked hard to make sure that Emily and I could continue, and could flourish, even under those circumstances.

When I wrote my eulogy for my mother, I asked my father to read it, and asked him whether there was anything he wanted me to put in for him, since he was not going to speak. He thought about it and said, yes: I want you to make sure on behalf of the whole family to thank everyone for coming.. So, on behalf of the whole family, in accordance with those wishes, I want to also thank each and every one of you for coming today.

It may surprise some of you to know that my father had a favorite poem. For all of his love of art and music and dance, for all his love of books and fiction, he wasn't particularly a poetry reader. But from when I was very young whenever the subject came up he would say he had a particular favorite poem. Appropriately for this occasion, it was a eulogy: the poem "In Memory of W. B. Yeats" by W. H. Auden. Here is a small section of it, which contains the particular bit he always pointed to when would ask him 'why is that one your favorite poem?'. As this passage begins, Auden is speaking of the day of Yeats's death:

But for him it was his last afternoon as himself, An afternoon of nurses and rumours; The provinces of his body revolted, The squares of his mind were empty, Silence invaded the suburbs, The current of his feeling failed; he became his admirers. Now he is scattered among a hundred cities And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections, To find his happiness in another kind of wood And be punished under a foreign code of conscience. The words of a dead man Are modified in the guts of the living.

My father's favorite line of this favorite poem was "He became his admirers". It appealed to his sense of postmodernist play, of course, and also fit with his essentially materialist world view. He liked the movement from the failure of flesh to the persistence what remains: words and thoughts. And I am sure that he liked that the suburbs are invoked in death and that cities are invoked in continuing life.

My father has now become his admirers. His words—the words he wrote, the words he spoke in class or in conversation, the words that he wove into his very own voice that started out as his, and now is scattered among a hundred cities—his words will be modified within each of us.

That was the end of the eulogy.

I am loathe to close, but have nothing more to say. I could fill up the infinite internet with words, and all my remaining days with quotations—and still it wouldn’t begin to grasp what is now gone, a loss that seems to transcend the mortal plane, to be beyond the world, where parallel lines meet.

A life.—His life.

I miss my dad. May his memory be for a blessing.

Apologia Pro Fructis Suis5

I have, as some of you will have noticed, not posted here for some time—my last entry was nearly two months ago. And those of you who are also following my story mosaic, Retcon, know that it too has been delayed (we are now overdue for the final two parts of movement one).

It would be untrue to blame all of this on my father’s final illness and death—I had already been thinking that a weekly post (with half of them substantial essays) was too much, and that I ought to cut back. And there were some old fashioned writing snags that played a big part in delaying the eighth story of Retcon as well.

But of course the fact that in the past two months my father was dying, and then died, and then had to be buried and mourned, and the inevitable errands that float around a death like the dust around a dropped coffin had to be attended to, all was a big part of what has happened. I will not say that my grieving is over (nor are the errands); but I am trying my best to move on.

I will not give a hard-and-fast schedule for either of my two ongoing writing projects; to set such a deadline would be to tempt fate. And I don’t think in any case that I will be trying to hit a once-a-week schedule here at Attempts in any case. So I will simply say that I am trying to restart, and that I intend (as before) to alternate serious essays and lighter posts, and that when they come they will (at least for the most part) come on Thursdays.

As for Retcon, the eighth and ninth story of the first movement will come as soon as I can complete them, after which the long-scheduled break will (alas) still need to be taken. But don’t worry that I have set aside the project or anything; the upcoming stories are coming as fast as time and I can collectively complete them.

Submit grammatical corrections in the comments.

As is all-too-true in other cases, the philosophical conundrum between worth’s universality and singularity, between universal love and the love that is theirs alone, is profound in the realm of grief. We recognize its universality and still feel, overpoweringly, its singularity. And no one (not Kant, not Aristotle, not Nietzsche, not Callard, not (certainly) that least-of-all I) have figured out a way to say both of those things at the same time

Plato, Phaedo, 118a, trans. Harold North Fowler; online here. I am always reminded of the words (from a much less lofty source) with which Arthur Conan Doyle had Dr. John Watson memorialize his best friend, “the best and wisest man whom I have ever known”. Doyle’s line must have been either a direct reference to Plato, or at the very least an unconscious borrowing. Doyle’s line is, however, rather undercut by the later retcon that Holmes was, in fact still alive: it was one of the great retcon—perhaps the first great retcon?—but it does rather spoil the line. Anyway, Plato got there first.

More or less. This is in fact a bit of a compromise version. I wrote a draft, and then emended it on the fly. Some of the emendations were purposeful and good, and I kept them; but there were also stammerings and missed words I have not reproduced.

I trust that someone will inform me if I need to follow this up with an apologia pro grammatica sua.

Stephen, Thank you for sharing with friends and strangers like me your eulogies and beautifully recounted memories of your parents. My thoughts are with you and your family this holiday season.

Terry Pitts