Contra Kriss on the Value of Truth

A follow-up to my essay about fiction and lies, considering the question of whether or not Sam Kriss is a liar

There is an old Yiddish proverb that “Man plans, God laughs” (Mann Tracht, Un Gott Lacht)1. I thought of this when I realized that my most recent essay had a direct bearing on a recent internet controversy—and that that controversy was in fact a test case for my argument. So this essay is a follow up to the previous one; it will help if you’ve read the earlier piece, but I don’t know that it’s strictly necessary.

First, a brief story.

Many years ago, just out of college, I worked for a while as a temp. In one job I was put in a small office with three other temps. We were doing something which was close to creative work: we were given a bunch of text and had to make it into restaurant menus (specifically those cards they used to put in holders on each table) and make it look nice. It was certainly the best temp job I ever had, which admittedly isn’t saying much. There even was a cassette player in the room, and we were invited to put on music to listen to while we worked. So we did, each bringing in tapes we liked and putting them on in turns. One day, fairly early on, I brought in a tape of St. Matthew’s Passion by Bach. We listened to one side of the tape, and then I got up and said, “Is it okay if I put on the next side?”

Two of my co-workers nodded amiably, but the final one—it’s been decades and I don’t recall his name, so I’ll just pick an arbitrary name and call him Sam—said, “Yes, I’d love to hear some more of that.”

Now he’d said it pretty flatly—no obvious sarcasm in his tone—but I was a bit concerned, since he did say it strongly enough that I was a bit suspicious. Since I was genuinely unclear whether he was being sarcastic or not, I said to him, “Look, we just met, and I don’t know you very well. I can’t tell if you’re being sarcastic or not. Did you mean that, or were you being sarcastic?”

“Oh no,” Sam replied, in the same flat, not-sarcastic voice. “I would like to hear it some more.”

So I flipped over the tape and put on the next side. About five minutes later Sam stood up, and said “I can’t stand listening to this any more,” and shut off the music. I was flabbergasted.

“I asked you if you were being sarcastic, and you said you weren’t, that you wanted to hear it some more!” I said.

“I thought I made that pretty clear,” replied Sam.

And that was it: another tape was put on, and nothing more was said. Not a big deal, and I was only there for a week anyway. But I thought at the time, and think today, that Sam was being an asshole.

Here’s the thing. It’s one thing to be sarcastic, and say one thing when you mean another; that’s an ordinary feature of ordinary human discourse. Very reasonable. But usually, to be sure, there is a specific tone that we adopt to make it clear what we’re doing. Yet Sam did not use a sarcastic tone, or at least I didn’t hear it that way—again, I didn’t know him, I wasn’t used to his way of expressing things. But perhaps I was paying inadequate attention and missed it, so I asked to be sure. And to then reply to a straightforward acknowledgement that I couldn’t tell if they were being serious or not with more sarcasm? That was just a willful failure to communicate well. Maybe, maybe, if we’d been old friends it might have made sense. But to someone who was, for all intents and purposes, a total stranger? Sarcasm is a reasonable convention; but when someone says I can’t tell if you are being sarcastic or not, it seems unreasonable to do anything but speak plainly. So: in my view, he was quite clearly being a jerk.2 Not the biggest deal: just a garden-variety bit of assholery, that’s all. Doesn’t mean he wasn’t otherwise a great guy, but it was a blemish, however minor. And hey, all of us can be assholes at times.

And the moral of the story is that sometimes there is not only a Gricean obligation to be clear, but a (admittedly low-stakes) moral obligation to speak clearly—at the cost, should one fail, of being an asshole.

About three weeks ago Sam Kriss, notable among substackers as a man who is doing successfully what I am doing marginally, namely, building an audience with sophisticated literary essays that aren’t meant as short comments on the topics of the day and which require a certain amount of effort to read, posted an excellent essay called The law that can be named is not the true law. It’s good; I recommend it. But it caused some controversy because the lengthy anecdote that ended the essay was, it turned out, entirely made up—although nowhere in the essay did he say this: it was presented straight.3 Which is the aspect that interested me: this was fiction without labeling—without the meta-data which, I claimed, is what properly distinguishes fiction from lies. So here was an interesting test case: was Kriss lying?

But before I weigh in on that question, let me clarify a bit when I am not talking about. Apparently the objections came largely (Kriss says entirely4) from the Rationalist community,5 and thus Kriss’s response (which I will address shortly) was mixed up with a great deal of critique of the Rationalist community more broadly. This is a topic I am not terribly interested in and one I feel I don’t know enough about to comment on (despite having read a number of works by Eliezer Yudkowsky6 and being a regular reader of Scott Alexander), but it is also, most importantly, an issue that is entirely besides the point. The Rationalists are a group which, as far as I can tell, a lot of people have really irrational reactions to, either wildly disproportionately positive or wildly disproportionately negative. Some people act as if they Invented Thought or are the Only True Knights of Reason; others think they are a creepy cult with sinister motivations and behaviors. Kriss, obviously, is in the latter category. Both of these positions seem to me ridiculous. It’s just a group of people—instead of a movement, it sounds at this point like more of an extended friend circle than anything else—a group with a subculture and in-group slang and common interests, much like any other group: it some good points and some bad points, like any such group, and presumably some good people and some less so. Why people get so worked up about it I don’t quite get.

But there is one thing about the negative reactions that I find irritating. Intellectual groupings are a useful shortcut to understanding a particular slice of the intellectual world, but it’s just that: a shortcut. It is often used, for both good and bad, to avoid some of the work of actually learning anything about the individual members: if you think you know something about the Romantic poets, you can avoid the harder work of digging in to the specifics of Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats, Shelly, Byron and Blake, noting their differences, their unique points good and bad, and so on. Like a wikipedia article, it’s good for an initial orientation but bad if you are going to, say, write an essay about a topic. Specifically, this is the function that the negative views of the Rationalist community serve to those who hold it: it lets people be dismissive of individual writers lazily, by ascribing views and actions to them based on other members of the community, or their vague impressions of other members of the community. Whereas the main thing I think about the two most prominent rationalists, Eliezer Yudkowsky and Scott Alexander—as well as other fine writers associated with the rationalists—is that they are both good writers and entirely different people. They each have their own style and their own viewpoint on things which differ from the others. Lumping them in as Rationalists is a lazy and intellectually cheap way to avoid reading their individual works and addressing their individual strengths and weaknesses. Of course if you don’t want to read them, you don’t need a justification for ignoring them: there’s too much out there for anyone to read; read what you want. But don’t pretend that you’re ignoring them on good grounds or claim that you know what they’re saying by appealing to a flimsy intellectual stereotype.

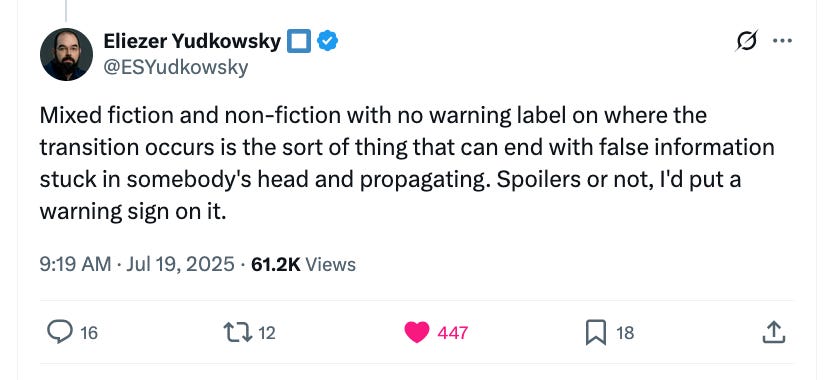

But Kriss describes (in his response piece) the reaction to his first piece as coming from the Rationalists, and (as far as I know accurately) describes Yudkowsky and Alexander as the most prominent rationalists, so let’s look at what they said about Kriss’s first essay (the links are via Kriss’s rebuttal). Here’s Yudkowsky:

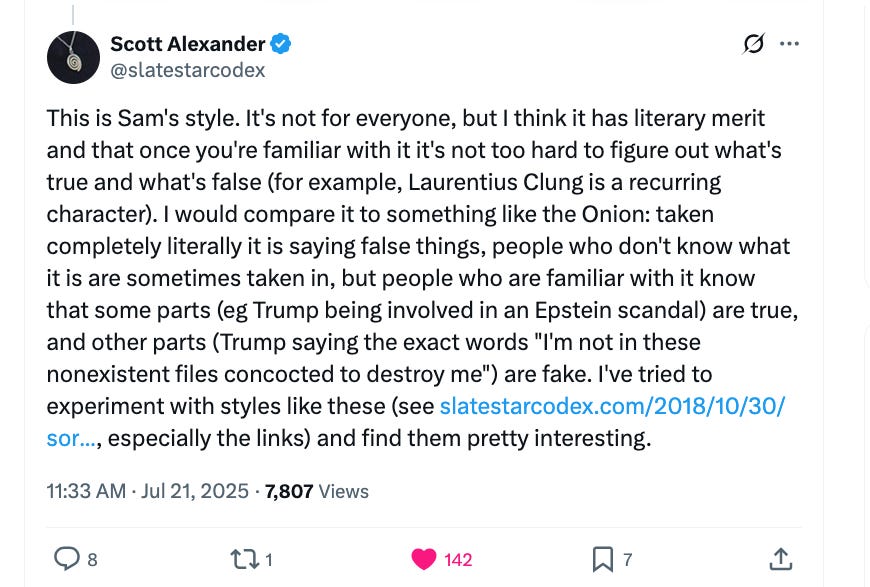

And here was what Alexander said on the issue:

Both of these points of view struck me as eminently reasonable, and in both cases quite mild. So if you do want to characterize the reaction of the Rationalist community as a thing (which as I’ve said you probably shouldn’t), then the reaction was a fairly tempered one.

Kriss, however, thought the reaction was not reasonable—and while he doesn’t link to any specific individual responses save those two,7 if the quotes he gives are accurate, then there certainly was some over-the-top responses to his essay, which is bad but sort of the kind of thing you expect on Twitter, even back when that was its name. But Kriss saw the opposition not just as some reasonable points with the usual sprinkling of normal-internet level unhinged comments, but as something particularly unreasonable and (I think) particularly nasty. I don’t doubt it was nasty—the net is a nasty place and it sucks—but I don’t see it as particularly nasty. More to the point, I don’t think the underlying arguments, stripped of the nastiness, were at all unreasonable. But since Kriss did, he responded with a follow up to his initial essay with another essay entitled “Against Truth”, complete with a “I don’t usually respond to critics, but—” disclaimer of the sort that anyone who has read many responses to critics will be extremely familiar with. In this second essay Kriss castigated the reaction to his first essay, not conceding that he might have acted imperfectly, nor attributing to his critics a difference in opinion about various abstract matters, but by doubling down on his righteousness, assaulting the basic idea of truth (really!) and, above all, assailing the Rationalists, because it’s easier to beat up on a group widely seen as weird and fringe than it is to actually defend an (at best) questionable position you’ve taken. And (to anticipate) it is more in this rebuttal than in his initial essay that Kriss really went wrong, even though his critics actually had, as noted, reasonable points.

So what is Kriss’s defense?

Well, his first move, as I indicated, is to quote some of the more over-the-top reactions, something which in the old blogosphere days used to be called “nutpicking” (a word that should be revived), which is sort of a weaker case of strawmanning: if strawmanning is making a weak version of an argument that no one actually holds, nutpicking is focusing on a weak version of an argument that only internet randos who aren’t worth taking seriously hold, and ignoring the more tempered (and sharper) criticisms from people more worth responding to. Then Kriss goes on to say the following:8

Even if I don’t usually like to break the fourth wall, I’ll do so briefly here, just to confirm that absolutely everything I publish is true. Laurentius Clung is a 100% real historical personage. He is not a metaphor, or my hyperbolic self-insert, or a device I use to extend an argument by illustrating important truths in a non-literal way; he was an actual theologian who lived and died in the sixteenth century… I first encountered Clung in Roland Bainton’s 1952 history The Reformation of the Sixteenth Century, where he gets two paragraphs in the chapter on Calvinism… He’s also discussed in the second appendix to the expanded 1970 edition of Norman Cohn’s The Pursuit of the Millennium, which is very much still in print and also great; if you haven’t already read it you should do so immediately… There’s substantially more on Clung in Blaire G Smellowicz’s Sodomites, Shepherds, and Fools: Minor Prophets of the Reformation, which is where I cribbed most of his more interesting quotes, and a very thorough but much less entertaining biography in Ander van der Gunk’s The Dutch in European Intellectual History, 1482-1648. (There’s also a complete scholarly edition of his pamphlets, letters, and diaries from Uitgeverij Verloren, but since it costs four hundred euros and I don’t read Dutch I haven’t been able to make use of it.)

What are we to make of this? Well, one thing to make of it is that—as best as I can tell—it is composed entirely of a series of false statements. The first few, however, are not clearly false, but are phrased in such a way that they look true: both Bainton and Cohn’s book are real. But a search on this electronic copy of Bainton’s book shows no mention of Clung, and Cohn’s book has (if Amazon look-inside is to be believed) but one appendix.9 After that the untruths get more blatant: if Smellowicz and van der Gunk are real people their work is unreferenced online save by Kriss.

Now, Kriss would presumably say that he was joking or being ironic, and that it should have been obvious. “Isn’t Smellowicz a dead giveaway?” he might say. He might also point to his next paragraph which lists blatantly preposterous (and therefore presumably obviously fictional) claims from his earlier essays. He would say, in other words, “I thought I made that pretty clear.”

But of course Bainton and Cohn are real, and their books, too. Of the myriad ways to lie, sliding from truth into lie is one of the trickiest to detect. And the next paragraph is, well, the next paragraph. Kriss has already slid from (presumed) truth to untruth before, in the very essay under discussion, so the fact that a paragraph of clear falsehoods could not be taken as having any clear bearing on whether the previous paragraph was true or not, and when I first read “Against Truth” I thought Kriss might be sliding from truth to reality in this case (and went to check out this Clung character). Which is to say, Kriss was following truths with untruths somewhere, either in his first or his second essay (in the first, it turned out: the second was all untrue), so he couldn’t pretend that the presence of later untruths made the earlier clear, since he clearly holds that mixing the two is alright.

After this, Kriss makes the following argument:

I would never lie about any of this, and what makes this allegation particularly offensive is that if it were true, there would be no precedent for the crime, anywhere in English letters. Reputable essayists do not introduce fictional devices into their texts, and definitely not when those texts are published alongside serious and sincere approaches to history, politics, ethics, and personal experience and tragedy. When Charles Lamb attributed the invention of roast pork to a Chinese boy called Bo-bo who accidentally burned down his house, he was basing this on the best available scholarship of his time. Since Thomas de Quincey claims to have revealed the contents of a lecture to the Society of Connoisseurs in Murder, maybe we should start searching abandoned cellars for their secret meetings. If Marshall McLuhan briefly mentions the ‘new spaceships that are now designed to be edible’ for no obvious reason, it’s because he was aware of something that NASA still won’t reveal. A propositional statement is either literally true, clearly marked as fiction, or a waste of everyone’s time. The purpose of an essay is to efficiently deliver accurate propositions, and any other features are only justifiable if they help the propositions go down more easily. On this point everyone has always agreed.

This is a defense of a particularly sophistic type—actually, of two. First he exaggerates the harm to make the charge sound ridiculous. “There would be no precedent for the crime, anywhere in English letters” is risible; but then, I strongly suspect no one said this (and even if someone did, they were being silly). Rather, the claim was that Kriss was guilty of a perfectly common, banal and yes, generally minor crime: lying. But it’s a lot easier to defend against a charge that is not being made, so that’s what Kriss does. And then, to further the point, he also exaggerates his opponents’ claims (that is, in addition to their charges against him), suggesting that they are claiming that things are “either literally true, clearly marked as fiction, or a waste of everyone’s time”. I very much doubt that that was said, either. But it’s a much easier charge to defend against than ‘you ought to put a warning sign on it’, which is what Yudkowsky actually said.

It’s worth noting that I, just to take one person, certainly wouldn’t say that the only choices are “either literally true, clearly marked as fiction, or a waste of everyone’s time”. In the essay I have referred to several times now, I mention all sorts of other cases of untrue speech that are worth distinguishing from both fiction and lies including exaggerations, metaphors, irony, jokes, mistakes, delusions, and bullshitting. But this is neither here nor there in this case, where the question is whether this particular untruth was reasonable. If the end of Kriss’s first essay was anything, it was a fiction—perhaps fiction used as a joke or a metaphor, but not a joke or metaphor in the plainest sense of the terms. It was an untrue story.10 And the question that people raised is ought it to be labeled as such?

—But wait, what about Kriss’s precedents? Ought we to conclude that Lamb, de Quincey and McCluhan are liars? What about ones he does not mention, like Swift’s modest proposal? Are they condemned?

But this, of course, distorts the issue several times over. First, there is the most likely possibility to keep in mind, namely, that Lamb, de Quincey and McLuhan did well what Kriss did poorly, and that to appeal to them as justification for what he did is like excusing anti-evolutionary creationist propaganda on the grounds that Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories did no harm. Second, while I don’t know for sure, I strongly suspect that if Lamb, de Quincey or McLuhan were asked about their essays, they would have answered clearly and plainly that the relevant parts were fiction. And, lastly, if both of those possibilities are wrong, then is there some natural law that great writers can’t have fucked up in this way? Great writers can fuck up in all sorts of other ways: writing bad works, most famously, as just about every great writer has done, but having terrible politics and being a terrible person are other common failure modes. So this particular defense of Kriss’s fails too.

So let us return then to the question of whether or not Kriss’s fiction was, because unlabeled, a lie, the question about which I wrote recently and whose relevance made me feel compelled to say something here. Was what Kriss did wrong?

In the case of his initial essay, I would say perhaps to a certain degree, but not terribly so. Essayists do invent things, although usually they are (or ought to be) either so over-the-top that no one ever thinks they are true (a possibly which the very hullabaloo around Kriss’s essay shows to be not the case in this instance), or clearly marked as such, at least in meta-data. Nevertheless, as Alexander says, this is Kriss’s style, and it is plausible to think that his readers recognize it and that any explicit marking is unnecessary.

—Or it would be, except that clearly not all of his readers do recognize it. In particular the rationalists who Kriss scorns became his readers when they read his essay, and they, clearly, did not know what was going on. “Everyone gets it” is just about always false—indeed it is usually said precisely because some people are not getting whatever “it” is being talked about, and the speaker is grumpy about that fact—but it is even more so nowadays due to the context collapse of the internet. So if Kriss was not quite wrong, he wasn’t right, either.

So am I saying that every fiction should have to be properly labeled, on the pain of being called a liar? Well, in my earlier essay I explicitly discussed cases where this wasn’t true, using the example of comedians who stick to a bit on interviews and talk shows,11 and since I believe that what I said then holds up, I am going to just quote myself (ellipsing things that make sense only in the context of the earlier piece):

I do think that commitment to a bit can go too far.... So call me a spoilsport or pendant if you like, but no, I do not think that “staying in character” is always justifiable. At the same time, I don’t think it’s always wrong, either.… I am claiming that any untruths called such in external metadata (even if that metadata is wrapped around a layer of fictional metadata that maintains the fiction) is fine, but that if you never break character you might simply be a liar—and that “everyone knew”, or “everyone should have known”, is not a defense… because it’s never strictly correct…. But if I am saying that this is also not always wrong, where then ought we draw the line?

I would suggest we… ask what would the effect be if everyone really knew (nudge-nudge, wink-wink) that the person was just staying in character. If it would simply extend the fun of the performance out into new arenas, drawing real live talk-shows into the fiction of a film or comedy sketch—if the power of that is not in people actually being fooled—then we can say that it is simply pushing the fiction on additional (admittedly possibly non-consenting) people. I don’t think this is then lying. That doesn’t mean it’s always ok—I think the closest parallel is something which is neither a fiction nor a lie, namely, playing a joke on someone: this is sometimes ok, and sometimes not, and it’s tricky and involves lots of judgment calls, but not because the categories are inherently complex but simply because specific applications of them are inevitably mixed with the complexity of the world (which is just to say that just because it is not lying does not mean it is okay: it might be wrong in other ways). On the other hand, if the staying in character would have no power if it were not for the deception—if the fun or the humor or the pathos or the arousal or the whatever-it-is that is being pulled out would misfire for an audience which knew, for a fact, that it was false—then it is lying, and no claiming that you were simply committing to the bit (or extending a joke) will change that.

Using that standard, I think we can clear Kriss of lying, mostly. Certainly he seems to have expected that his audience would see it as obviously false, and that it would do its work anyway.12 So he was not intentionally lying, and if lying requires intentionality, then he wasn’t lying. At the same time, Kriss seems to have been wrong about its effect: first, because a lot of people weren’t able to tell, and, more importantly, because the fact that they read it as true affected the way they read it such that they afterwards felt betrayed. I don’t think that Kriss should necessarily have anticipated this, but I do think that, once it turned out to be the case, he ought to have reacted differently than he did—and, say, cheerily put a warning label on the top of the post, rather than defensively inveighing against truth as a value.

That said, while I said before (and stick to) the idea that not every untruth needs to be labeled in the meta-data or be a lie, I do think that that would be a very reasonable standard, and possibly a better one in the age of internet context collapse than it was when Lamb, de Quincy and McLuhan were writing (indeed, McLuhan himself might have a few things to say about this particular aspect of the matter, given that it is about the difference between the. mediums of print and of the internet13). I certainly don’t see what the harm would be, and it would be much better for the health of our communal discourse. Yes, you could say of satire from The Onion or Babylon Bee being pulled out of context and believed that “it happens”, and it does—but honestly it’s a bad thing that it happens and I don’t see how it benefits art or sophisticated discourse or truth or anything else not to mark things satire. The main charge against it, I think, is that it is clumsy and unsophisticated; but that strikes me, frankly, as a price worth paying. It really doesn’t mean that much more than that people who think them selves too sophisticated to need such labels—people like, presumably, Sam Kriss—will need to endure the half-second effort to skip over that line of text. In previous days, spitting and pissing in the street used to be common, but at some point the mixture of better knowledge of sanitation and new living conditions (urban density) made possible by social and technological change made it clear it shouldn’t continue, and progressive campaigns were waged to instill (successfully, in the U.S. anyway) the new habits. I think a parallel effort on behalf of “always label satire and fiction” would be a good one, tamping down a habit which might have been ok in earlier settings (although even there it’s a bit gross) but certainly now ought to continue. But since this new social standard wasn’t in effect when Kriss wrote, I don’t think it’s fair to charge him with having violated it.

But even if you don’t think everything needs to be labeled, it seems to me that it is at least inarguable that things that people are clearly in the process misunderstanding ought to be given a label in retrospect; and further that one ought to not lie again in one’s defense of having mislead people—even if you think you were “perfectly clear about that”. Which is to say that if Kriss’s initial essay was not necessarily a bad thing, his response to the hubbub about it it was.

And it’s worth noting that my judgment here seems to have been pretty much along the same lines as the main response Kriss actually got. No one, as far as I know—and at any rate no one sensible—said Kriss should not have written his first essay on the grounds that it was untrue. Just to take one example, Yudkowsky said, in the tweet I already quoted, no more than “I'd put a warning sign on it”. He also followed up (replying to Alexander’s tweet quoted above) with an even more moderate suggestion:

This is an even more minimal demand—the linker should be a warning on it. As I’ve made clear, I myself think that his first suggestion was reasonable: there’s no reason not to tag parts of the piece fiction. If everyone is supposed to be able to tell, then it does no harm to note it explicitly. If on the other hand acknowledging it as a fiction weakens it, then this is due to the fact that it is deceptive (at least in part: perhaps the power comes from uncertainty about where the truth ends and the fiction begins, as I discussed in the “based on a true story” case in my earlier piece). But the idea that the linker should flag it is also quite reasonable—and if the linker doesn’t know it’s half fiction, well, then that returns us to the idea that Kriss should have flagged it himself in the first place.

And personally I would make an additional and even more minimal demand: that if you are going to mix fiction with truth, and people get upset, just own up to the fiction. Don’t lie in your defense against the charge that you’re a liar. Is it likely to fool many people? I have no idea. But it makes Kriss, just as it made Sam, an asshole.

What do I think Kriss should have done? Honestly, just said, “whoops, my bad, I thought people would be able to tell/knew I did that sort of thing”, ignored the more deranged critiques, and put on a warning label. It’s not a mortal sin; but that doesn’t mean it’s just fine and dandy, either.

I have only discussed the opening of Kriss’s rebuttal essay; the remainder of it is on other topics, not precisely relevant to my discussion here. After the bit quoted above, Kriss veers into a lengthy attack on the Rationalists, which, as I said, is neither here nor there, but which as best as I can tell is thoroughly tendentious; if you believe it, I have a copy of the complete works of Laurentius Clung to sell you. And in particular he attacks Yudkowsky’s fan-fiction Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality, which has its faults, but Kriss so overstates them as to make his criticism utterly dismissible—nothing in Yudkowsky’s book is as bad as Kriss’s reading of it. I won’t claim that HPMoR (as it is abridged) is perfect by any means, nor the Greatest Book Ever Written; but to make a more apt comparison, I will claim that it is much, much better written and thought-out than any of the seven Harry Potter novels by J. K. Rowling, which certainly seems the apt point of comparison. (If you’ve only read the canonical Harry Potter, give it a try; bear with it for the first few chapters, though, since it gets better as it goes along.)

Kriss then ends his essay with a lengthy critique of utilitarianism, which is not particular new to anyone who has read critiques of it before, but shows (in his casual dismissal of Bentham, Mill, and many others) that he does not suffer from intellectual humility. He castigates Rationalists for seeing utilitarianism as “obviously true”, and uses as his argument the fact that only 21.4% of professional philosophers hold to it, never showing any concern over treating it as obviously false when more than 1 in 5 professional philosophers hold to it. I’m not saying utilitarianism is right—the arguments against it have some merit—but Kriss makes them so dismissively and arrogantly as to undermine the actual value they have.

One further note from the latter part of Kriss’s second essay is worth touching on. In the course of his rant against the Rationalists, Kriss attacks them for a simpleminded notion of truth. I don’t know whether or not it’s an accurate depiction of rationalist beliefs (Kriss has given us absolutely no reason to take his word for it, or even to take his opinion as having any weight whatsoever, because this is what happens when you lie and then complain when you’re called out about it), but having read Yudkowsky and Alexander gives me reason to suspect that Kriss’s characterization of Rationalists is in fact a straw-man. But on the off chance Kriss is right, then yes, the rationalists have an overly simple view of truth—yet Kriss’s reply to that error is itself fatally flawed. He writes:

The rationalists are wrong about many, many things, but it’s precisely in their wrongness that they express an important truth about the world: that large parts of it are made of something other than plain facts, and the more you insist on those facts the wronger you will be. I love them, in the same way I love the Flat Earthers and the people who think the entire Carolingian era was a hoax... In their instrumental aspect, they are my enemies. But I still don’t want them to stop believing what they believe, or to start believing what I believe instead. I don’t even want them to stop accusing me of lying. I just want them to have a little perspective.

Kriss’s claim that “large parts of [the world] are made of something other than plain facts, and the more you insist on those facts the wronger you will be” is, I think, an example of what Daniel Dennett dubbed a deepity: a statement whose apparent profundity comes from its being ambiguous between a claim that is weak, banal, and true and one that is strong, shocking, and false. Are there fictions in the world in the sense that people tell stories about people like Laurentius Clung, and those are part of the world? Yes, obviously. Do symbols and values and judgments and other things which aren’t “plain facts” also make up part of the world? Again, obviously so. But does that mean that being clear, in making claims of fact, about what is true, what is fiction, and what is false is unimportant? Obviously not. This is, like so much of Kriss’s response, an attempt to dodge a question, presumably because confronting it would put him at the distinct disadvantage of defending obviously unreasonable conduct and claims.

On the other hand a sense of perspective is certainly a reasonable request. So (although not a Rationalist, and therefore not one of those of whom he specifically makes the request), let me do my best on that score.

Is Sam Kriss a liar? Yes. Not in his initial essay (which is a borderline case, but which as I said falls on the right side of it, in intention if not in actuality), but he was in his follow-up. This is not, to my mind, a particularly close call. More importantly, he was certainly wrong to be so aggrieved and defensive that people objected to his misunderstanding about whether people would recognize his fiction as such. To take the most generous case, if Kriss did think it really was obvious (which I suspect is true), and that he would care if he fooled people (which I am far from certain is true), why would you not just reply with something on the order of “oops, sorry”? That he defended his misapprehended fiction seems to imply that he either did want to deceive people, or (more likely) didn’t care if he did, or at least was so scornful of people he considers unsophisticated that he doesn’t at any rate care if he fools them, at least until they have the temerity to object to it on Twitter, in which case he feels affronted.

But while Kriss reacted badly, and even (in his second piece if not his first) a liar, he is not a terrible one, nor an indefensible one, nor one in any way that would vitiate his power as a writer or his insight as an observer or even the value of that particular essay. He is mostly guilty of a casual disregard for whether his fictions are in fact fooling people. There is a sin, here, but it’s minor—and wouldn’t be worth noting if Kriss hadn’t been so defensive about it. Kriss is guilty only of a misdemeanor, not anything more serious. And the only punishment is, more or less, self-inflicted: Kriss was, in his follow-up piece at least, being an asshole: and that is the entirety his punishment, that he was an asshole. Ideally, he should suffer the further punishment of recognizing that fact, but I have little hope in that. But it is true nonetheless.14

Kriss, presumably, would point out truthfully that this was a minor sin—but that is not a defense; nor is it a defense against a minor sin to pretend that you are being accused of a major one. Kriss would also, presumably, argue that it his initial untruths should have been obvious. But this goes to highlight a point I made in my earlier piece: that the problem with “everyone can tell” is that it is nearly always false. Certainly you can’t rely on “everyone can tell” when defending yourself against a bunch of people who, in fact, could not tell.

Kriss might argue instead that everyone ought to be able to tell—probably in the form of accusing those who couldn’t of being stupid or uncultured. I don’t think that’s true at all, but even if it is, I don’t think it’s a defense. Are we supposed to not care about what stupid people think? I think we ought to. Even aside from the obvious political reasons (stupid people vote, too), there’s a basic moral case to be made here, one that is so obvious it seems petty to point it out, except that apparently it still needs to be said. (Telling someone not to piss in the street sounds ridiculous, but if people start doing it again we’ll have to.) Put simply, “you shall not… place a stumbling block before the blind.” (Leviticus 19:4) is a perfectly sound moral principle. This is not to say that everything has to be pitched to the lowest common denominator; but some appropriate labelling seems quite little to ask. And the most worrisome part of Kriss’s conduct, to my mind, is that he seems to feel he did nothing wrong, even unintentionally, even after it was shown to him that people were misunderstanding him. I suspect that his true fault is less being a liar than being someone contemptuous of those who think differently (in particular, not as well) as he does. Which, in the end, is just another way of being an asshole, I suppose.

I definitely think that Kriss is still worth reading. But speaking for myself, I wouldn’t trust any fact he gives on any topic without checking it. For most writers that would be a genuine loss for their own ability to express themselves, but I don’t know if Kriss, given his attitude about truth and what I fear is his disdain for some of his (at least one-time) readers will care. If he does care, however, it is a problem entirely of his own making: if he is going to stick to his guns that fiction need not be labeled, need not be plainly and clearly admitted to after the fact when called on, need not be divided from fact such that a essay on (presumably) true things can slip unnoticed to one on false things, then not being taken seriously on factual claims is a very predictable consequence. Which is to say that even though Kriss has done nothing particularly wrong here, he has done something mildly wrong, and those have consequences, too. If he doesn’t want this to happen—if he actually wants to be understood, and to have his factual claims (when he makes them) taken seriously—then he ought to take Yudkowsky’s very reasonable advice and “put a warning label on it.”

Let me end where I began: Kriss’s initial essay was quite good. And the fiction that makes up the last part of it was particularly good. I’m glad he wrote it. I don’t think that accurate meta-data would have diminished it; and given that, there really is no argument for not putting it on. And certainly you should know, going in, that at least the second half is fiction, and that I have no idea how many untruths are in the first half, or indeed if anything he says there has the slightest basis in reality. But on one level, it doesn’t. matter; I still recommend you read it. Laurentius Clung is a fiction, but I wouldn’t hold that against him; whatever his faults, he’s the protagonist of a charming tale that’s well worth reading.

Which was beautifully misquoted by Milan Kundera in The Art of the Novel (chapter 7, The Jerusalem Address) as “Man thinks, God laughs”, which as far as I can tell isn’t a parallel saying but simply a misquotation, but which I like equally well, and differently, than I do the original.

My memory is that I asked the other two at some point when Sam was out of the room, and they were non-committal, presumably not wanting to get involved in a dispute between two people they didn’t know, which was fair enough.

I think it was only the end that was made up—but the truth of the matter is I don’t know, and I haven’t investigated the matter, and given everything I wouldn’t place any weight whatsoever on the fact that Kriss wrote about it. He might, I imagine, be perturbed about this—he was making a political point, he might care that people took it seriously—but if so, that is simply another argument for accurate meta-data, and one that he might take seriously since its deleterious affect is on his own work. (Of course, might also not care that people disbelief everything he says; if that’s the case, I still think he should be clear about it, but I can’t say that it’s strictly in his instrumental interest.)

Save for a response by noted far-right political commentator Curt Yarvin, who is not a Rationalist.

The contemporary group, that is, which is not to be confused with the seventeenth-century philosophical movement.

Which, unlike Mr. Kriss, I would recommend: not that they’re flawless (what is?), but they are definitely, in my view, worth reading.

And the aforementioned one by Yarvin, which is more of an aside.

I have elided the boilerplate snark about how not all knowledge is online, and a few other asides, but you can read the entirety at the link if you wish.

I’m not going to buy it on Kriss’s recommendation, since that recommendation occurred in the course of a lie and I don’t know how seriously to take it.

Note that jokes are usually labeled—”Let me tell you a joke”—and metaphors embedded in larger claims not presented as free-standing stories, unless those stories are also fictions, or parables, or the like: which means that in addition to being metaphors, they are fictions.

I didn’t specifically discuss a situation quite like Kriss’s, but the two types of case are parallel and the same remarks apply to both.

Of course, as I discuss in the earlier piece, there is the problem that nowadays people—more politicians than substackers—will say things hoping to fool someone and only ex post facto excuse it by saying “everyone knew I was joking” or, even more insidiously, hoping that half their audience would write it off as a joke and half take it seriously. There is no reason to think Kriss was doing this: but not wanting to be associated with this quite vile rhetorical technique is a reason to take more seriously than Kriss does the. value of explicitly labeling fiction as such.

If only I happened to have him here.

An apology or sense that he’d gotten this wrong would vitiate even that, but it too seems too much to hope for.

if a golfer wanders onto a football pitch while a game is being played, and one of the footballers tries to pass the ball to the golfer, and instead of taking it the golfer is hit painfully in the groin, that is nonetheless not a violent assault