Prefatory note: It is fitting, I think, that this first substantial essay on Attempts (2.0) is too long for email; it presages accurately what I am doing here, which includes writing without fear or favor of words limits. If you are reading these words in an email, what you will see below is only the beginning of the essay; you need to click through to the web-browser version to read the rest. I hope that the opening will entice you to do so.

The reading life of every serious reader is shaped by the happenstances of juxtaposition and order, far more than we usually give thought to. We praise the pacing and structure of an author's book, and approve or not the contents and course of a professor's syllabus, but for our larger readings we are all followers of Saporta and Cage, drawing at whim from the deck standing on our shelves. How can we pretend it doesn't matter? To reverse two chapters in a book will present each in a different light: the subtle consequences of knowing or not knowing that when you reach this makes all the difference. If two seemingly unrelated tales or theories are placed beside each other, we look for connections. To be sure, the pacing and strands in a book or syllabus are intended and therefore, we hope, more meaningful than what we might get from casting sticks or flipping coins: but does that mean we see nothing from the juxtapositions of chance? The curator's art is a subtle and underappreciated one: but the very fact it relies on, that each sculpture reflects, at least a little, some light from the one across the aisle from it, means that we can glean some things from fortuitous groupings as well.

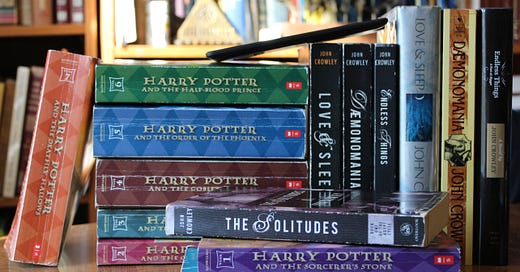

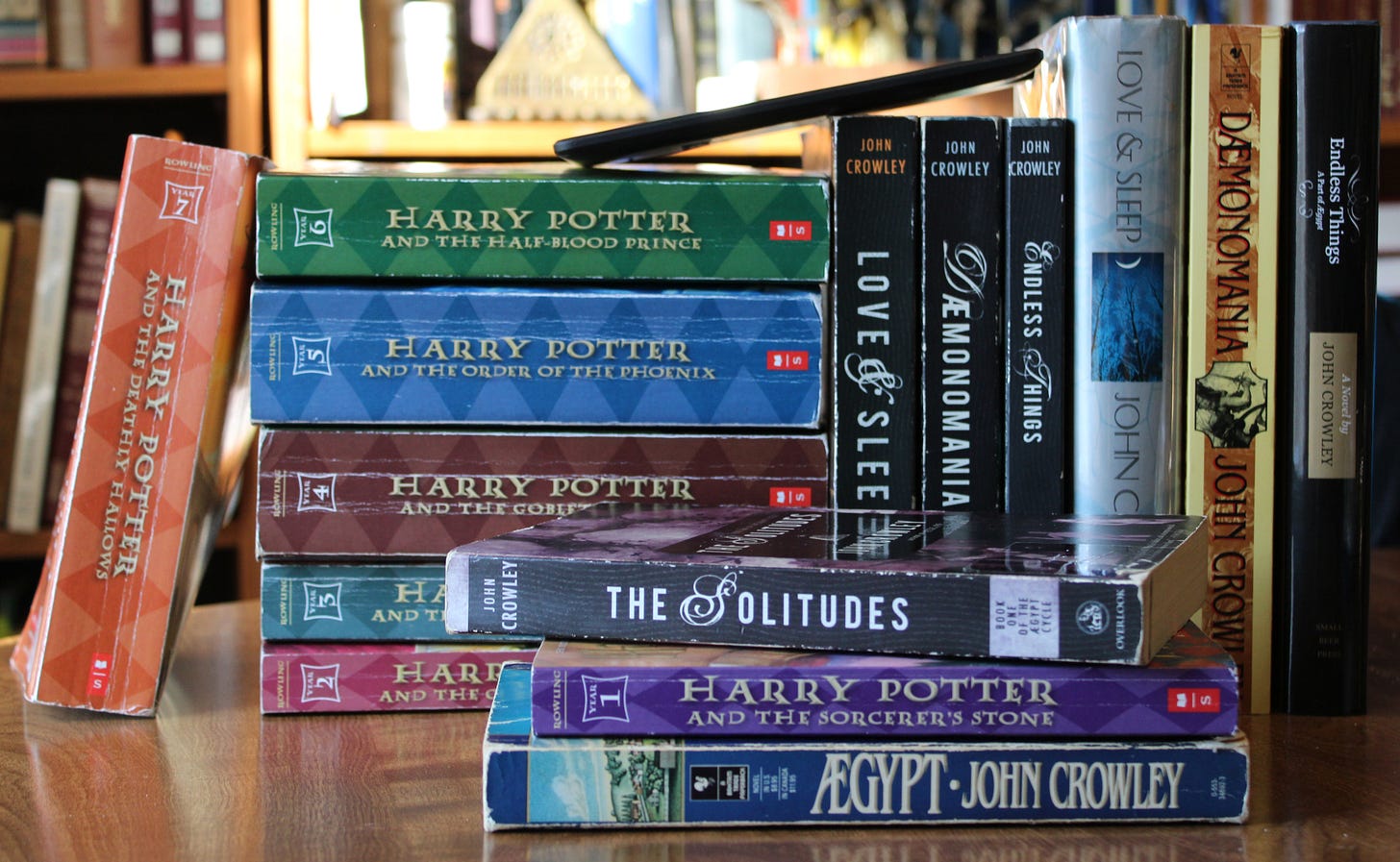

Some time ago I happened, due to a chain of fairly arbitrary decisions, to read concurrently two series of books about magic and its students, bouncing from one to the other frequently but not in any regular pattern. The reasons were personal: I had promised my then-eight-year-old that I would read the Harry Potter series (which I had not previously read) along with him, which meant that I would put it down and wait for him to catch up when my edge of more than three decades’ extra experience as a reader would slide me more swiftly through. And I had decided (again, for personal and fairly whimsical reasons) to reread the longest work of one of my favorite authors, John Crowley's four-volume novel Ægypt. I would read Crowley until my son pulled ahead of me in Rowling, switch, pull ahead of him in Harry Potter, and then return to Crowley.

It was a juxtaposition that highlighted each books' nature with fierce and beautiful clarity.

But while the Harry Potter books are now as widely known as any set of books save the Bible, perhaps some introduction of John Crowley's Ægypt is in order.1 Ægypt is a single novel, published in four volumes over the span of twenty years; the individual volume are The Solitudes (1987),2 Love & Sleep (1994), Daemonomania (2000) and Endless Things (2007). The concluding volume came out in the same year as the final Harry Potter book. Crowley's novel is a fantasia on various beliefs about the world now understood to be untrue — the physics underlying the researches of the alchemists; the geocentric cosmos believed in by the ancients, with its literal seven heavenly spheres; the beliefs about Egypt which (at least according to historian Frances Yates, whose work underlies much of Crowley's novel), while erroneous, were nevertheless a crucial factor in the course of the early Renaissance. Ægypt's conceit is that all these ideas, now seen as disproved, were in fact once true, but that at various key points in history the fundamental nature of the world changed, and changed so thoroughly that not only was the present of the universe remade but its past was as well, so that what had once been the case now had no longer ever been so. In dramatizing this notion, Crowley's novel focuses primarily (although not exclusively) on two time periods. Much of the work is set in the late 1970s, centering on a fictional part of the northeastern United States called the Faraways;3 the principle protagonist of these sections of the novel is a failed historian named Pierce Moffett, but there are a large number of other important characters as well, and in particular a woman named Rosie Rasmussen has a fair claim to be co-protagonist with Pierce. Another large portion of Ægypt is set in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries in Europe, again including many characters but with the two principle protagonists being two historical figures: John Dee, the astrologer, alchemist and court magician to Queen Elizabeth, and Giordano Bruno, a philosopher, writer and forerunner to modern science burned as a heretic by the Catholic Church in 1600. Connecting these two periods are the researches and writings both of Moffett and of a (fictional) novelist named Fellowes Kraft, whose estate Rosie Rasmussen is in charge of and whose works may perhaps make up (the exact ontology is intentionally slippery at times) most of the historical portions of the novel.

That brief summary may make Ægypt seem to have nothing at all to do with the Harry Potter series. But in fact, as I read them in tandem, a genuinely incredible number of similarities presented themselves.4

Both are fantasy books set in a version of the real world, and not a fully-created secondary world such as is found in The Lord of the Rings or A Game of Thrones. Both involve British magic, expanding out to other places too, a magic that is forgotten by the ordinary world (in the Rowling, because Obliviators rush to the scene and magic away the memory of any muggles who witness it; in the Crowley, because the nature of the world changes and turns what had been magic into something else). Both involve main characters who, for initially mysterious reasons, end up being raised not by their fathers but by their uncles (and aunt, in Harry Potter's case; and mother, in Pierce Moffett's), and both have a cousin or cousins who grow up as, essentially, siblings. Both involve a philosopher's stone — secreted away and then destroyed in Harry Potter; sought but unfound, attempted but not successfully made, in Ægypt. Both have a werewolf as an important but clearly secondary character. Both involve extended flashbacks (although more extensive in Ægypt): flashbacks to the past of the characters in the Rowling, and the past of the world in the Crowley (although each does a bit of the other too). Both contain a fair amount of Latin. Both centrally involve the mystery of a small, abstract figure made of lines and circles (the symbol of the Deathly Hallows in Harry Potter; John Dee's Hieroglyphic Monad in Ægypt). Both deal with the fate of the world, which is in some sense saved in each book.

In addition to the larger connections, reading the two series in tandem (in a way that, absent parenthood and promises, I would never have done) drove home all sorts of smaller coincidences which are probably meaningless, but which nevertheless continued to claw to the forefront of my reading consciousness. Take the final volume of each series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows and Endless Things: both have epigraphs where all the previous installments in their respective series did not. Both include wedding scenes, attended by but not involving the central character. Both spend much of the book away from the main setting of the previous installments (Hogwarts, the Faraways), as the main characters go off on a quest of sorts. Both end with a chapter in which several of the main characters reunite after many years, along with much-grown children.

Then there are the deaths. A substitute father-figure to a main character dies in the antepenultimate book in each series (Sirius, Boney). In the penultimate book of each, a great wizard dies near the end, assassinated by repressive forces, but with a certain help or cooptation by the wizard in question (in one case regarding who actually kills him, in the other in allowing it to go through unhindered). Both of the wizards return—sort of, after a fashion (but after different fashions)—in the series' respective final volumes.

Reading in tandem, it's hard to know how seriously to take any of this. Is it mere coincidence, no more meaningful than the fact that both authors have the sequence of letters "r-o-w-l" in their surnames? Is it that both draw from and play with the same traditions of legends, which guide their respective tales along parallel lines? Is it simply that any two book series would have so much in common, that the structure or pacing of a series requires such coincidences? Yet they rain down. In Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, we find the titular character shadowed by a mysterious, large, black dog; that same dog (now explained) is pointedly described in a later volume as "dogging" Harry. And then, in Daemonomania, we read this: "…Pierce, just then sensing something behind him to be afraid of, half turned to see a large black dog, just steps away, following him silently, dogging him: red tongue awag, and eyes like coals. MEPHISTO, Schwarzer Pudel, uncommonest of his shapes." (479)

The fireworks: I read the firework scene in Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix and the firework scene in Love & Sleep within a day of each other. The Rowling is definitely more, well, like a firework show: loud and spectacular with bursting and garish colors. It is a fun interlude of revenge against a hated foe. The Crowley scene, on the other hand, is quiet, filled with painful irony and the set-up of future heartbreak. — But let us take this opportunity to turn here, as those two particular scenes also capture the essential difference between the two books.

For despite a list of similarities and parallels that could be significantly extended, the two books are, in fact, extraordinarily different. On at least one reasonable axis along which one might plot fantasy literature (or simply contemporary literature in general), they are on opposite poles. They differ in style, in texture, in the nature of their plots, and in the nature of the reading experiences they offer.

Rowling is exciting; Crowley is enthralling. Rowling is a page turner; Crowley is a breath-stopper, which forces you to look up from the page, again and again, aghast at the beauty of his vision. Crowley's characters are vividly realized realistic portraits, with all the nuances of real people; Rowling's characters are cartoonish, although this is their strength as much as it is a critique: cartoons are far more memorable in many ways than the complex faces of actual people. Rowling's books, despite taking place during a succession of school years and thus being (ostensibly) a slice of life, read as adventures; Crowley's books walk with the unsteady gait of real life, without the predictable climaxes and reversals of adventure stories. Rowling's books are widely used by young children as a gateway to reading; Crowley's books require a fair amount of prerequisite knowledge in order to properly enjoy them. Rowling's books have been made into highly successful movies; Crowley's are almost certainly unfilmable.

Some of this can be put down to their intended audiences: Rowling's books, although read and enjoyed by a great many adults, are written as YA novels, if not straight-up children's books;5 Crowley's books are decidedly intended for adults — and not, simply, because of the sex scenes that he includes, although there are a few of those.6 Crowley's novel requires an interest in topics (history, child-rearing, complex metaphysical systems, broken relationships) that is rarely found in children. Similarly, the pacing of Ægypt is slow, the richness within it to be found in the majesty of the prose as much as the grip of the plot: and this, too, is a taste more common in adults than in children.

So this is the explanation for some of the difference, perhaps— but not all, or even most of it. Because there are plenty of books for adults (at least in the sense of having the sex scenes, and of being about topics intended for grown-ups, if not the same sort of topics as Crowley's) that are decidedly on the Rowling side of the spectrum. Page-turners, cartoonish-characters, filmable plots: these are not absent for books shelved quite distantly from the YA aisle in your local library. The differences go beyond audience into both the style and the concerns of each book. Consider, for instance, the related issues of the nature of the worlds each book is set in, and what the reader might learn about those worlds in the course of reading.

Despite occurring (ostensibly) in our world, the familiar world with London and telephones and the Oort cloud and octopi in it, the Harry Potter series unquestionably creates a world: it is even called "the wizarding world" in the books. This is a "world" in the sense of a subculture, of course—as we might speak of the literary world or the Orthodox Jewish world—not in the sense that, say, The Game of Thrones or the Narnia books take place in another world (a secondary world, as it's called by fantasy readers). Still, the creation of the world is one of Rowling's genuine achievements, and a lot of the fun of the books is in mentally exploring that world: finding out how they do things (what do wizards use instead of telephones?), working out inconsistencies (why did the wand "kill" Harry in the forest but then refuse to later inside Hogwarts?), and so forth. We ask questions about what happened to characters after the books' end or before they began, some of which Rowling obligingly answers in later interviews (Umbridge went to Azkaban; Dumbledore was gay), others of which become material for fan fiction.

In contrast, Ægypt, for all its fantasy, explores our world. The Faraways is a vivid place; but it is hard to imagine extensive follow-up questions being asked about it. (Although I, for one, would not have minded a map.) Crowley's characters are subtle and complexly drawn; but one does not wonder in great detail about their lives before and after. There is, to my knowledge, no fan fiction about either the places or the people of Ægypt. On the other hand, Crowley's observations about life and personality ring true for us, here, in our world, with the people we know and are. The fictionality of his world is not a landscape or a construct but a conceit.

And we are, in fact, likely to learn a lot about our world—in particular its past—by reading Crowley. To be sure, we will need to do careful research if we want to know precisely what is true and what is not, since Crowley so carefully interleaves his fictions into the genuine history also presented. Some work is required to find out that (say) Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is a real book but the Ars Auto-amatoria was invented by Crowley.7 Which details of Dee's and Bruno's life are wholly fictional, which groundedly speculative, and which attested, we might not get straight. But all save the most well-read reader will come out of these books knowing more about how our world is and was. Even the magic represents (at least in part) real beliefs about the past, even if their actuality is (we must presume) imaginary.

History plays a powerfully different role in the two series. For most of Harry Potter, history is trivial: Hermione's reading of Hogwarts: a History is a running joke, and the History of Magic professor is the dullest in the school, and it is clear that the course is of no importance (Harry's worst grade in his O-level exams, a "dreadful", is in the history of magic, but there's never any indication that this is of the slightest consequence). History of a sort takes on a slightly more important role in the final two volumes, as the history of Voldemort that is uncovered in volume six is essential to his defeat, and the history of the deathly hallows in volume seven is important to the plot as well. Still, it is history of an extremely limited and personal sort. Further, nearly all history events referenced in Harry Potter are fictional history (even though it occurs in the real world): various magical wars, personages, laws, and so forth, are mentioned, but for the most part the discoveries, conflicts and changes in real human history are not. (There is a hint that magical events might be behind certain real events, such as the possibility that Grindelwald was involved in the course of the Second World War, but this of course tends to heighten the focus on unreal history, rather than bring true history to our attention.)

In contrast, Ægypt is steeped, even saturated, in real history. History books (in particular those of Frances Yates) are cited in the text. Historical sources are quoted verbatim. Real historical figures and events are portrayed. The departures from history are within the cracks left by the historical record, in the same way events in many novels with a contemporary setting (Ægypt included) relate to the real world: they are snuck into the corners and gaps. The death towards the end of the penultimate volume of Harry Potter is a shock to the first-time reader, a moment of genuine suspense and power; the death at the end of the penultimate volume of Ægypt is a well-known historical event, known to anyone who recognizes Bruno's name (which the text seems to presume will be everybody),8 and is, therefore, powerful but hardly suspenseful — indeed, most readers will have been anticipating it since early in the first volume. Even this, however, underplays the involvement between Ægypt and history. For it is not just that Ægypt includes historical events and personages: its very matter is about history's nature and flow. History's process in every sense — its discovery and writing, the course and cause of its events — is one of the central subjects Ægypt treats.

Both Rowling and Crowley's books revolve around mysteries, but the nature of those mysteries are utterly different. Rowling's are mysteries in the sense that murder mysteries are: there is an unknown thing, which some people know but which our protagonists do not, and then, through clues and accidents and patience, the protagonists uncover them. The mysteries are things such as "what is on the third floor behind the locked door?", "why did Harry survive the killing curse?" and "where is Sirius Black and what is he trying to do?" Answers to all these things are provided, usually within a single volume, but at any rate always by the series' end. Upon a rereading, every mysterious thing in Harry Potter would be clear — every unusual emotion given an explanation, every half-heard conversation provided with a clear context.9 In Harry Potter, mysteries are solved.

In Crowley's Ægypt, on the other hand, the "mysteries" that are present are mysterious not in the sense of murder mysteries, but in that of religious mysteries. They are fundamental, inscrutable, numinous. In Crowley's novel, a fundamental ontological uncertainty is foundational to the narrative: precisely what happens, what has happened, is in places obscure, possibly up for grabs. One of his recurring techniques is to narrate events — for a paragraph, a page, on occasion close to a chapter — and then take it back, say it didn't happen, leaving us uncertain if that was an alteration in the world (of the sort the novel is about), or a dream, or mere narrative tease. Ambiguity, metafiction, and perceptual limitations are all used to make the world mysterious. To simply solve these mysteries would be to miss the point.

This distinction is not absolute: there are some puzzles in Ægypt which clear up on a second reading — a number of mistaken identities (a plot device which recurs several times over the four volumes) are a prime example, as is the reason Pierce was removed from his father's custody. But there are many more mysteries, the more fundamental mysteries, which are not like this. And the converse is not true: nothing in Harry Potter is fundamentally mysterious. There may be specific questions unanswered, but ignorance of circumstances and numinous mystery are fundamentally different phenomena; Harry Potter trades on the former, Ægypt on the latter.

But perhaps what most clearly differentiates these two similar, utterly different books is one of the central matters upon which they most notably overlap, the thing which will put them (to the extent that they are put) side-by-side on the shelf set aside for fantasy: magic.

For the magic in the two books could not be more distinct.

In Rowling, the magic is dependable, regularized, and understood. If it is mysterious the first time it is encountered, it is reliable the second, and all but unremarked upon thereafter. We are told, clearly, what magic can and cannot do, what is and is not magic. Even the single bit of magic that starts out as slightly numinous — the love that enables Harry to survive the killing curse — is, as the books go on, made clear, its the rules explained, and finally it is employed a second time, at the series' end.

Rowling's world replaces technology (or anyway that significant subset of technology which is used by muggles but not wizards) with magic, in ways that highlight the latter's nature as the former in wizarding drag. We have loudspeakers; they have magical spells to amplify a human voice. We have guns; they have killing curses. We have antibiotics; they have healing potions. Rowling's characters use magic routinely: it is part of their ordinary activities, used for cooking and cleaning and daily transportation. The effect is to make magic unremarkable, the way that future tech in science fiction is intended to be unremarkable: apparition is as routine as Star Trek's transporters, and as likely to produce awe (as opposed to plot complications).

Rowling tries to avoid this, to some extent, by making Harry (unused to the wizarding world's ways, especially in the early volumes) a proxy for the reader, showing his marveling and mystification when confronted by the magical things he (and through him we) see for the first time. But the overall effect of these introductions is to make the mysterious familiar: what starts out as mystery becomes ordinary, so that the polyjuice potion which is difficult and dramatic in book two becomes a minor plot point in book four, and then a routine threat to be guarded against in book seven — by which time it is no more mysterious than the existence of cell phones or automobiles. It is simply one of the things that exist in that world. Similarly Gringots, the wizarding bank, which is presented as an exciting place with at least a touch of wonder in volume one, becomes, by volume seven, simply the setting for a bank-heist story. At his first encounter with a new magic, Harry is often stunned (actually, at times stunned long past when he should be: don't you know you're at a wizarding school, son? Why are you so surprised when a chair unfolds into a wizard?) But he, and the reader, take it in stride the second time.

The magic in Rowling is, of course, taught: indeed, it is the defining characteristic of the series that she takes many elements from previous fantasy literature (wizards, wands, potions and the like) and places them in a British boarding school. What this means, naturally, is that the magic is teachable: ordered, regular, predictable in its uses. It is dependably masterable. If a spell is difficult or unreliable, that requires some explanation — the wizard in question is particularly bad at that one spell, or is using a wand not their own, or some such.

The magic in Ægypt is wholly different. It is elusive, mysterious, numinous. The magic presented in Crowley's novel is constantly being narratively undermined: some of it is implied to simply be a fictional conceit in the book-within-a-book (we think by novelist Fellowes Kraft) that we are (probably) reading. Other sections cut away at a crucial moment—say, the opening of an ancient, mysterious, long-impenetrable chest—in such a way that while we are led to believe that some great secret might lie within, we are never quite shown it, never allowed to be sure. Some transformations are held up as possible delusions, or as the equivalent of religious beliefs, so we are never entirely certain if what we are seeing in the narrative ought to be taken straight or just understood as an extended metaphor.

Is the werewolf portrayed in Ægypt a literary creation of Fellowes Kraft? An actual, historical werewolf? A dream that someone (really) had? A metaphor for a mundane state? A thing that people in the early modern period believed, but falsely? Something that used to be true but now not only isn't but never was? (It's even unclear how to distinguish some of these possibilities.) It's not at all clear that there is a stable, resolved answer to these and similar questions in Ægypt: it is intentionally ambiguous, with the wonder, the magic, residing in the possibility that cannot be ignored yet at the same time can't be grasped or nailed down. It is, in fact, in the mystery that the magical manifests.

In Ægypt, the senses of the word magic meaning a mysterious power (as in a magic wand) and that meaning a trick (as in a magician at a birthday party) are entwined: we, the reader, are never quite sure if we are being tricked, or if we are being shown something unworldly, a metaphysical miracle. We receive hints of the magical, like scents of a wondrous thing, which, turning, we cannot see. Crowley's magic is only visible, if at all, in the edge of our field of vision: look straight at it and it disappears.

The magic is so elusive, in fact, that at least one generally insightful reader put aside the book frustration halfway through the first volume, complaining that the author seemed scared of fantasy, was avoiding the magic, and was writing something which, for most of the text, resembled "an extended artsy slice-o-life story from the New Yorker". It is true, I think, that Crowley is afraid of magic: but not in the way that the disappointed reader suggests. He is, rather, afraid of getting too close lest it spoil the mystery — afraid the way a magician would be afraid to let you watch their trick from behind them, where the palmed card can easily be seen; and, simultaneously, afraid the way any sensible person would be afraid of a potent and volatile explosive; and, finally, afraid in the way that genuine metaphysics seems terrifying — the terror that we feel in the face of either God or His absence.

And while Crowley's magic is off-stage, ontologically suspect, ambiguous, and far less fun than Rowlings, it is, simultaneously, far more mysterious — which is to say, far more magical. Rowling's magic, for all the wonders she shows, is not nearly so wonderous.

Any sufficiently developed magic system becomes indistinguishable from technology. As the rules are laid out, formalized, schematized and listed with the precision of a RPG manual, the sense of them as magic becomes purely formal: it's magic because we call it that, because it uses famous symbols such as wands and muttered incantations, and because its authors do not bother to apply the tricks of the pen necessary to call it science fictional technology. But once you have rays of colored light shooting at dodging foes, does it really matter if they come from a wand or a ray gun?

To be sure, Rowling's magical system is not quite as developed as some. She does not itemize points of magical energy that deplete and must be renewed, nor construct elaborate rule systems detailing what is and isn't allowed. You couldn't quite simply play it as written within a game of Dungeons & Dragons. But the difference is, finally, slight.

Magic in Harry Potter resides in particular people, who form a subculture: there are wizards, squibs and muggles, and the first of those form the wizarding world, with its own newspapers and towns and laws. It is a place: and if you know the right trick, you can get to it. Like any place and people, it is only strange when unfamiliar. We become accustomed to its ways. In Ægypt, magic is not in particular people, but in the nature of the world, or (perhaps) of our perception of it. It is tried and failed; it is vanishing; it may never have been there at all.

Perhaps we might say that the two books contain two different things, both of which are plausibly named "magic" (which is to say, both of which are similar to and derived from previous uses of the term) but which have almost entirely disjunct natures.

Crowley's magic is, finally, magical in a way that Rowling's is not —elusive, unfathomable, hovering between a grand metaphysical reality and a mere trickery of language or light. After all, magic is, by its nature, mysterious: that is what unites wizards and stage magicians. The strange, inexplicable power of the former is not radically different than the sleight-of-hand trickery of the latter: it is that intersection which creates the meaning of the term "magic". Once we know what process creates an effect, it no longer is magic, but simply a tool, or chemistry. To put someone under a spell is both to trick them and to manipulate them in inexplicable ways: the notions are inseparable.

What are we to make of this stark, undeniable set of differences, when placed aside the equally stark, equally undeniable set of similarities? After all, if it were simply a matter of being intended for a different audience, or written at a different literary level, we might expect the differences, but not the similarities.

The answer, I think, is that the works share roots, but have taken very different elements from the same tradition. Both are works of western fantasy: but what that means, what that leads them to do, are almost entirely different. Rowling takes the elements of fantasy, and presents them as adventure; Crowley takes the feeling of fantasy, and presents it with the content hovering just out of sight. These are both genuine inheritances from the tradition of fantasy literature; it is as useless to ask which is truer to that tradition as to ask whether Jack Spratt or his wife were truer to the platter they together licked clean.

In a sense, of course, both books use the furniture of fantasy; that is the explanation for the overlapping werewolves, philosopher's stones and so forth. But Rowling employs much more of it. Indeed, some of the fun of her books is seeing the familiar wands, potions and flying brooms in such ordinary circumstances, so that the first may be bought, the second taught as recipes and the third used as gear in a popular sport. The familiarizing of magic in Rowling is not (or at least is not just) a flaw: it's part of the fun. It allows us to imagine ourselves into the world, since, after all, we too buy things, follow recipes and play sports. The taming of the mysterious is itself a pleasure.

What Crowley takes from the western tradition of fantasy is subtler. First and perhaps most importantly, what he does is return that tradition to its roots: he traces back things which have been tamed (long before Rowling) by their appearances in fantasy trilogies and role-playing games and, by putting them in their historical context, simultaneously makes them more real and defamiliarizes them. At the same time he takes the sense of the unknown, and the unknowable, which lies at the core of fantasy's deepest impulses — the dark forest whose darkness and mystery is essential in making it not simply another cluster of trees — and recreates it for a time when we feel as if all the forests have at least been google-mapped, if not actively logged. Fantasy arose from mystery, from the blanks on maps and unplumbed darks: now we know too much for it. Crowley undermines our certainties and thereby returns the wonder.

But if that is what Crowley draws from the deeper historical roots of fantasy — the actual, once-living tradition of alchemy and centuries of witch hunting — there is also something he draws from more modern fantasy, and that is a powerful sense of loss.

Fantasy is, or often is, about the disenchantment of the world, the thinning of modernity, for which science is the strand of modernity most centrally responsible. A great deal of twentieth century fantasy, in particular, is laden with a pervasive sense of melancholy — a sense that critic John Clute calls "thinning". It beset by nostalgia and loss: by our time, the wonder of the vast wood has gone away. The great things that occurred in the past (the past that we are reading about) have now faded into mere myth and legend. This sense, the sense that the world has been tamed, that the richness of mystery has been replaced by the rigor of science — this is, precisely, what Crowley is writing about. And it was really science that did it. Yes, the elves departed Europe as the forests were cut for lumber, the dwarves left England as the hills were split for coal: but it was science that has thinned the world. Crowley's Ægypt is about this thinning: the rise of science, the decline of magic and wonder. His magic vanishes when mystery does, because magic fundamentally is mystery.

Rowling's magic, on the other hand, is not replaced by science; it replaces science, each missing technology having its magical counterpart (thought magic has more: it is the technology not our world, but of a cartoonish SF, of The Jetsons or Back to the Future 2). It is at home in the modern world, for all its quills and parchment and owl messengers. What wonder it has is the wonder of early SF: "now see THIS technological marvel!" — that is to say, the wonder of novelty, which always stales overnight. Mostly, though, Harry Potter is not wondrous but exciting.

Rowling is fantasy in the indicative: things happen. People feel. What is mysterious is cleared up, explained, resolved — definitively and unquestionably settled. Crowley is fantasy in the subjunctive: maybe, perhaps, seemingly, apparently. It is in questions — could it be? What if it were? — not statements. The entire series hangs together in a questioning mood of elusive possibility.

What are we to make of these differences, these two distinct drawings from the same dark well?

Some people will want to say the Crowley's is a better book, because it is subtler, truer to life, more magical, with far more gorgeous prose. Others will want to say the Rowling is better, because it is more exciting, more fun, presents more starkly delineated characters, and a great many more people like it. But I think the truest answer is that they are simply good at very different, almost non-overlapping, things. One gets literary whiplash going back and forth. To read one is to engage in a very different activity than reading the other.

It is more than a matter of different pleasures. Umberto Eco wrote in his Postscript to the Name of the Rose: "The ideal reader of Finnegans Wake must, finally, enjoy himself as much as the ideal reader of Erle Stanley Gardner. Exactly as much, but in a different way." And this is true in its fashion. But I think even to flatten the variegated emotions summed by the various books into the single, monochromatic word "enjoy" is to miss the mark.

I fear I may be coming across as denigrating Harry Potter; nothing could be further from my intentions. The thrill Rowling has created in millions of readers, above all in children, is itself thrilling to behold. To create wonder and delight is itself a wondrous thing: the worldwide enthusiasm for Rowling's work is quite a magical feat. The books' charms are straightforward, but its charm is not. The best spell of Harry Potter is the one it casts on its readers. It is Rowling, not Dumbledore, who is the wizard of the Harry Potter story; it was not Voldemort but Rowling who really took over the world.

Why is Rowling so much more popular than Crowley (indeed, than just about any other fantasy author)? A great many of the reasons we have already covered: to be children's as well as adult literature is, definitionally, to broaden one's audience; to be exciting and fun is an easier sell than to be poetic and enlightening. And, of course, we must not omit the single biggest factor in any successful artwork's fate: luck.

But a few other features also bear mentioning before we close.

First, many of Rowling's virtues invite the reader's own imaginings. As I already noted, to put magical items in ordinary contexts is to invite us to imagine them in ours; similarly, to create a world is to invite readers to explore it. Adventures hold out the possibility of more adventures: we can imagine ourselves in them, and, if we are children, run around a field of grass with picked-up sticks for wands, playing wizard, and making a numinous magic of our own.

But, above all, Rowling's books are easier, in a great many ways. We have mentioned that they are written for children, with all the relatable characters, simpler prose and bigger dollops of sugary excitement that that implies.

Yet it's not just that. For when I say that Rowling's books are easier to read, I didn't simply mean for others: I mean for me, as well. Moving from Crowley into Rowling was far easier than the reverse. Rowling sucks you along; Crowley resists, and expects you to push. Crowley's book is more work. It is work that pays off with unparalleled richness: but is a work that, necessarily, few will be willing to do.

Rowling's books fit better into the contemporary pace of our lives: they are quicker — more quickly paced, more quickly gotten into, their pleasures easier to access and readier at hand. A subtle palette is hard to return to after the bright contrasts of a starker one. Rowling has the pleasures of the simple, the quickly relatable; Crowley has the pleasures of the difficult. Both pleasures are genuine; but the former are, definitionally, easier to access: more people, and all of us more of the time, are ready for them.

Further: the simpler is more universal. Excitement is a more international language than poetry. There are, to be sure, those who find themselves left cold by Rowling's books. But Crowley, dearly loved as he is by many very fine readers, is a specialized taste. Even a great many of his most intense fans will confess that they initially had to give it several tries before getting into his works. Crowley is one of my very favorite authors, and while many of the readers I most respect would say the same, many other readers whom I equally respect (and who are no less knowledgeable in the tradition he writes from within) find him unreadable.10 He is strange, and strangeness is always specialized.

But there is still yet another thing, one that goes far beyond the specificity of taste as well as beyond the complexity of prose and character, the compulsiveness of page-turning. Even with the realms of the poetic, Crowley can be hard to access: for Ægypt is a book with prerequisites.

Rowling draws from the western tradition in a way that introduces readers to it. My son didn't know that basilisks are ancient legends dating back to the Roman Empire, whereas dementors are Rowling's invention; he didn't need to know.11 Readers who meet basilisks in Rowling can discover their earlier incarnations when and if they read the Monster Manual or Pliny's Natural History. But Rowling introduced them perfectly comfortably. For a great many readers, wizards and wands and potions and broomsticks will go together because of Rowling: she will become the biggest node in this network of transmission.

Crowley's books, on the other hand, require, for their enjoyment, a significant familiarity with the history and literature of what we might (somewhat quaintly) call "western civilization". A fair amount is explained, but a much larger amount is not. I have already mentioned that Crowley seems to assume his readers will have heard of Bruno; of how many people, even just considering devoted readers, is that true of these days? Likewise a sense of the general course of the scientific revolution, of the rough nature of monarchy and alchemy and a thousand other things, are more or less required to surefootedly navigate Crowley's tale. Nor are more recent developments exempt: a notion of what the sixties were and what they meant is presumed rather than explained in Crowley's book.

This is true not only in the grand course of the narrative, but in the minute texture of the prose. Consider the following sentence: "He drove with stately care out the long grassy path that in winter would be snow, another thing that Pierce, like the Grasshopper, chose not to ponder now in the golden time." (Daemonomania, p. 68) Aesop is not cited; to those who do not know the fable, the invocation of the (capitalized) "Grasshopper" must be mysterious indeed. Perhaps, to people of Pierce Moffett's generation, that fable was still a fairly central part of common culture. Yet having had, in my teaching career, to explain a great many fairly obvious New Testament references to purportedly Christian undergraduates (and me an atheist Jew!), I have to doubt that it still is. And it is, notably, a reference that will not be readily uncovered by googling: if you don't know it, it requires some work to get at it. Now obviously this one allusion is a passing one, which can easily be left behind as a modest textual mystery; many readers, presumably, will simply miss it. But how many of these can a reader encounter before they put aside the book as closed to them? For that matter, how much of the genuine beauty of the text will simply escape a reader's notice, for want of a context against which to see it?

Halfway through Endless Things, the novelist Fallowes Kraft thinks of his last, unpublished book, musing that it is "A book that even if he finished it would be too long for anyone to read, and would still have to be read twice to be understood." (183) This is the same book excerpts of which (seemingly) make up part of the text of Ægypt itself: in a strict and literal sense, this is a comment on Ægypt by Ægypt. And, it is hard not to think, a commentary by Crowley on his own novel (a portion of which had already been in print for two decades, and which had appealed to decidedly fewer readers than I imagine he wished).

If Harry Potter is for many the beginning of reading, Ægypt may be for some few the terminus of it: a book to read, not as a first portal into a fantastical world, but as the prize that awaits at the quest’s end. This is not to say that no reading will follow: every quest ends, of course, with happily ever after, and how can any true reader live happily without a bountiful supply of ever-more-wonderful books? Still, there are hardships that must be braved before Ægypt is reached: or, at the very least, a lot of prior journeys. And unlike the happy quest narratives that Harry Potter both resembles and departs from, not everyone makes the trip successfully. Some don't get to the prize at the end.

And maybe — on this particular quest, which requires some esoteric and specialized knowledge increasingly crowded out in our culture as history lengthens; as, in particular, common cultural literacy extends in breadth (an extension which is both inevitable and necessary due to the demands of justice), and therefore, simultaneously, inescapably, lessens in depth in the spots previously focused upon exclusively—fewer and fewer will. There may be more than one history of the world: but there are limits to how many any of us will have time to come to even a moderate familiarity with.

Ægypt is a melancholy book in many ways (notwithstanding the fact that there are a great many moments of joy and transcendent wonder in it). But what is particularly melancholy — all the more so as it is a real world melancholy which resonates with the melancholy within the text — is that it is not clear how many more readers of Ægypt there will be in the history of the world. I could not escape thinking, at times, that I myself might be the last one. I don't actually think so, any more than Pierce Moffett believes his own crazy notion that the world used to operate according to different laws than it now does. Not really. But the sense of thinness, of loss, which so much fantasy speaks to,12 that in Ægypt is connected to the loss of the mystery of the world brought about by science (a familiar melody in writings on modernity, first introduced as Max Weber's "disenchantment"), is connected for the reader, or at any rate for this reader, with the loss of the culture which makes Ægypt possible. We modern Grasshoppers are too busy with our iThingies and our memes to attend to the old and mistaken writings of alchemists or the outdated fables of Samosian slaves: we certainly have little time for long, poetic books whose world-ending catastrophes are mysterious and metaphysical and hinted at, rather than written boldly in the sky by a group with the rather unsubtle name of the Death Eaters.13

Everything ends; the new cultures have their richnesses too, and avoid many horrors of the old. Yet perhaps we can take a moment to mourn the gods and constellations that we ourselves have slain: to see the sadness in the ruins of things once great, the now-gone, once-endless things upon whose remains we have built our evanescent world.

Over the years of his early childhood, as I watched our son grow, I fervently hoped that he would become a reader: not more than anything (not more than that he would be healthy, be happy, be kind), but more than almost anything. And these days being a reader as an eight-year-old is nearly — not precisely, but nearly—synonymous with loving the Harry Potter books. So it is not inaccurate to say that for years I wished that my son would love these books — books I had not at the time myself read, but which I trusted would be enthralling and magical, and which would contain above all the magic of reading. They were, for which I am forever grateful. And I am gratefully fortunate that my son became the reader I hoped he would be.

To like Crowley's books is a harder thing to do, and definitely a more adult thing. It requires a patience with slow books that is hard for anyone, even a dedicated reader like myself, to summon in these twitter-attention times. It requires a specific taste, a taste even many readers of long, slow books turn out to lack. And it requires a familiarty, an interest in (if not a knowledge of) a western tradition that is increasingly less a broad inheritance than a oddball subculture, one probably smaller than those who attend pseudo-Medieval entertainments, or who knit seriously, or who read longish essays on fantasy novels. No one can reasonably hope that any particular person will acquire all of this. To wish that for that would be to wish that they become someone pre-set, and not who they are wont to be: which is, after all, what parents truly want, or ought to.

Yet if my now-happily-fulfilled hope for my son's becoming a reader was that he read and love Harry Potter, I can't help but wistfully hope that, in his adulthood, his life may follow a course such that he may read and equally, although differently, love the mysterious, heartbreaking wonderous beauty that is Ægypt.

About the Potter series, I need perhaps merely specify that I am discussing only the original seven novels, not apocrypha such as Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, Forbidden Beasts and Where to Find Them, and the like.

The first volume of Crowley's four was originally published under the title Ægypt (that is, the individual volume was given the name of the overall work); it was later republished under the originally-intended title The Solitudes. Ægypt remains the title under which you will find the excellent audiobook version of volume one, narrated by Crowley himself, which is highly recommended, despite the inevitable disappointment experienced when, having reached the end, you recall that the only the first of the quartet has been recorded, and the remainder one must read for oneself. Although originally issued by various different publishers, all four volumes of Ægypt are now in print from Overlook Press; the Overlook Press edition also incorporates some revisions to the earlier editions, and is to be preferred. (Subsequent citations are to those editions.)

I took it to be upstate New York, where I live, and indeed it has some similarities; but Crowley has pointed out in an interview that not only is the place not specified, but that at least one detail in the work deliberately makes any precise extant location impossible. The book is set in a northeastern state that is not Massachusetts, nor New York, nor Connecticut, nor any of the others we know.

While I shall discuss at a length both the similarities and the differences in these works, there is one difference, arguably a fundamental one, that I intend to gloss over. Crowley's Ægypt is very much one novel, divided into four volumes just for publishing convenience; Rowling's Harry Potter series is very much seven novels, sequentially dealing with the same characters in the same world and with many ongoing themes and plots carried from one to the other. Despite the artistically crafted individual shapes of Crowley's volumes and the undeniable links between Rowling's, this is unquestionably a distinct difference. But to the accidentally juxtaposing reader, it means less than it might seem. Each series flows from one book to the next; the story of Harry Potter is no less of a whole than that of Pierce Moffett. Certainly now that both are complete, both will henceforward typically be read as wholes; and continuities and identities notwithstanding, I would guess that more readers will stop after The Solitudes than after Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. So I shall let this one distinction slide, and refer to each set (somewhat inaccurately) both as a series and as single, unified books.

Probably the best way to put this is that the early volumes of Rowling are children’s books, and the later volumes are YA.

And it will perhaps clarify what I mean when I describe Ægypt as a novel for adults when I say that the sex scenes in it are generally far more disturbing and unsettling than actually erotic.

Although we are warned by the author's note ("To the Reader") that prefaces The Solitudes that "…the books that are mentioned, sought for, read, and quoted from within it must not be thought of as being any more real than the people and places, the cities, towns, and roads, the figures of history, the stars, stones and roses that it also purports to contain." (5) Everything about that warning—its poetic flow, its playfulness, its necessity— all speak to the difference between Ægypt and Harry Potter.

It is interesting to imagine a reader coming to Ægypt without having ever heard of Bruno, but it's hard to believe that such a reader would make it through all four volumes.

The unsolved mysteries of the sort that prompt fan fiction and readerly speculation are not deliberate puzzles but rather unintended flaws in the fabric which need to be filled in or unknotted.

Although none of those readers have (to my knowledge) even attempted Ægypt. Crowley's most famous book, and nearly always the first that a potential reader of his attempts, is his immediately prior novel, Little, Big (1982). Prior to my second reading of Ægypt, I would have said that Little, Big was his finest work. After my second reading (at the time I first drafted this essay) I would have said that Ægypt is. Now I have thrown up my hands at the question, and will simply declare that Crowley has written four masterpieces—Engine Summer; Little, Big; Ægypt; and Ka: Dar Oakley in the Ruins of Ymr—all of which are beyond the event horizon where litterary merit can be sensibly compared.

Of course I told him anyway.

Although, again, and notably, not at all the Harry Potter books.

Few, I fear, will even have time for long essays upon them: if you have gotten this far down, Noble Reader, and even essay the footnotes, you are a special reader indeed: I am grateful for your attention, and hope you feel moved to return for future essays on equally esoteric topics.

"It is interesting to imagine a reader coming to Ægypt without having ever heard of Bruno, but it's hard to believe that such a reader would make it through all four volumes."

It's not hard for me: I was just such a reader. Ægypt (as the first volume was then called) was my first aware encounter with Bruno, and with John Dee; and it was moreover my first substantial engagement with the history and thought of the Gnostic sects, the Hermetic Tradition, Renaissance philosophy, and alchemy beyond the facile and stereotypical "lead to gold" motive. The invitation and opportunity to learn more about all this, which I also took up in the numerous books on all these subjects and more that now strain my shelves as a result, was captivating, and propelled me eagerly through each of the subsequent volumes as they appeared. In addition, of course, to the superb prose and deeply engaging characters.

I should add that, though much younger when I first read Ægypt (I was in college), and pursuing a technical degree (computer science), I wasn't entirely historically illiterate. It's just that my attention in that realm was much, much more focused on the classical and medieval periods, and took little notice of the Renaissance beyond the highlights hit by my high school A.P. History class.

I also had this side-gig going in Tolkien studies....

A wonderful take on these books. Thank you very much. Very enlightening indeed. Myself I had the opportunity to read Mr. Crowley's works one by one as they appeared. Pure coincidences. I am in the Stockholm area, Sweden. And to find these books I really would have to go into the big city, visit a few main bookstores who'd eventually have a little pile of them. I ain't in town all too often and by sheer luck when I've been to them stores now an' then, lo an' behold, a new work by John Crowley! This happened all the way from Engine Summer unto Lord Byron's Tale (KA I finally ordered.) What I wished to convey here really is that when I came to the end of Aegypt I had the sense that I had read a complete book ... and then many years later Love and Sleep arrived. Such a surprise! Well, thanks again for the essay. Lovely writing by the way.